They only knew her as Bena.

To a tight-knit bunch of Rainey brothers raised under wide Texas skies, Bena was their no-nonsense grandmother—the kind of woman who could silence a room with a look and spit a stream of tobacco into a spittoon twenty feet away without missing. She didn’t talk much about the past, and by the time they were old enough to ask the right questions, the answers had long been buried under years of silence and fading memory.

What they didn’t know—and had never been told—was who their grandfather was. Not his name. Not how he met Bena. Not even how he died.

What they did inherit was a whisper of family legend, passed around at reunions and in front of old woodstoves like worn-down folklore: that Bena had killed her husband. Or maybe it was her father who did it. Or maybe both. The details changed with the telling. Some said it was a crime of passion, others suggested it was a matter of justice—or vengeance. But there were no records, no obituary, no grave. Just a blank space in the family tree and a story too suspicious—and too intriguing—to ignore.

Somewhere between the hollers of Oklahoma and the old cattle trails of East Texas, the truth was waiting. This is the journey to find it. A genealogical trail ride through census rolls, marriage ledgers, county histories, and death records—one that uncovers not just who Bena really was, but how a forgotten man, and the generations he left behind, nearly vanished into obscurity.

Bena, the Cokers, and the Raineys

Bena McWhorter was born on December 14, 1898, in Beaumont, Texas, to Julius McWhorter and Ada Howard (source: Texas Death Certificates, 1903–1982; Burnet County #84468). By 1904, Ada had remarried to William Edward Coker, and the blended family eventually settled in northeast Henderson County, somewhere in the vicinity of Brownsboro—an area dotted with longstanding Coker homesteads going back to the 1850s.

William Coker’s family ties reach deep into East Texas history. His father, George Washington Coker, was part of the early pioneer movement into Henderson County, and his grandfather, James Coker, helped establish roots in the region before the Civil War. But it’s the other side of the Coker tree that opens the door to Bena’s hidden connection to the Raineys.

William’s uncle, Nathaniel Green Coker, married Mary Ellen Rainey in 1894. Mary Ellen was the daughter of Wiley A. Rainey and Mary Ellen Young Rainey, a couple who had migrated into Henderson County likely in the early 1890s. This union made the Cokers not only kin by marriage to Bena’s stepfather but also in-laws to the Rainey family—creating a tight web of overlapping surnames, properties, and relationships across the region.

In short: the Cokers connect both lines. They link Bena to the family of her mysterious future husband—making it all the more possible that what began as neighborly association in rural Henderson County may have quietly blossomed into something more… and eventually, into the dark family lore the Rainey brothers grew up hearing.

After nearly a decade rooted in Henderson County, Texas, the Rainey family joined the wave of settlers heading north into the newly admitted state of Oklahoma, which had gained statehood in 1907. By the time of the 1910 U.S. Federal Census, Mary Ellen Young Rainey, now a widow, was living in Ravia, Johnston County, Oklahoma with her two sons—John H. Rainey and Luther C. Rainey—as well as her aging mother, Virginia L. McAdams Young. The family patriarch, Wiley A. Rainey, had passed away the year before, in 1909, leaving behind a legacy tied to both the cattle trails of Texas and the tight-knit rural communities he helped settle.

Meanwhile, Bena McWhorter—now in her early teens—was living several hundred miles south in Robertson County, Texas with her extended blended family. Residing in the household of her mother, Ada Howard Coker, and her stepfather, William Edward Coker, Bena shared the home with her half-siblings: Thorberry Coker, Irvin Coker, and Earnest Coker, and her half-sister, Fannie May Coker. Though physically separated by distance, the McWhorter-Coker and Rainey families remained socially and genealogically intertwined through their shared roots in Henderson County.

Given these enduring ties—and likely facilitated by family visits, correspondence, and reunions—Bena McWhorter eventually formed a relationship with Luther C. Rainey, the youngest son of Wiley and Mary Rainey. Their courtship may have unfolded during one such visit back to Henderson County, where their extended kinships crisscrossed through the Coker lineage.

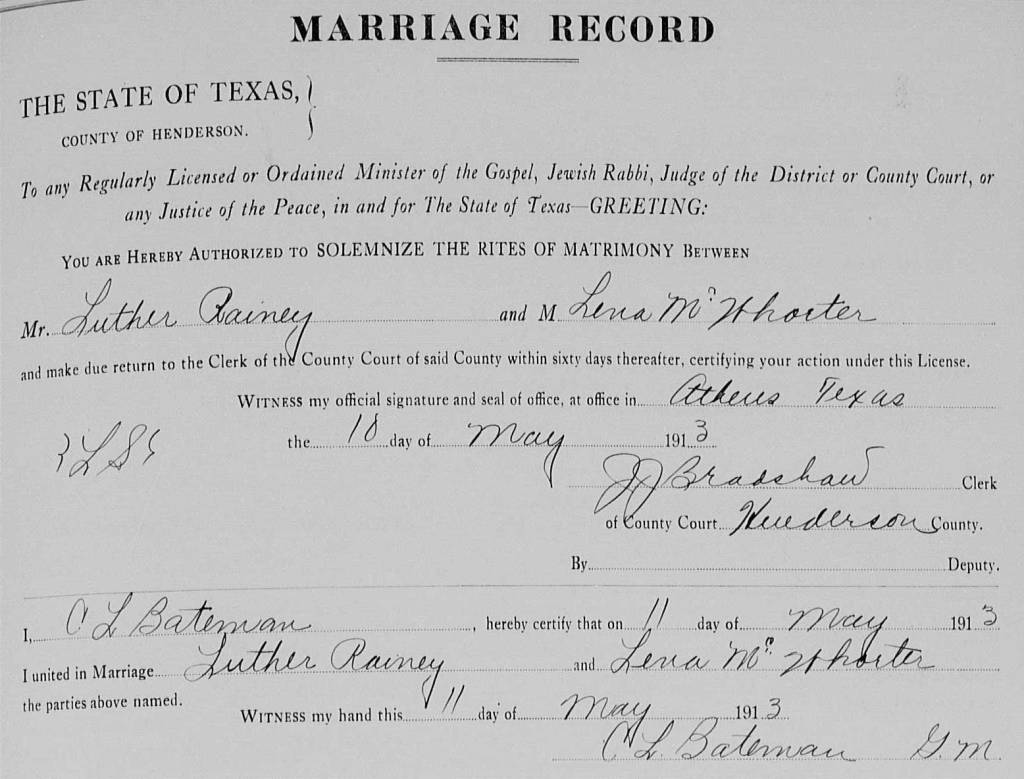

On 11 May 1913, fourteen-year-old Bena married eighteen-year-old Luther in Athens, Henderson County, Texas—a union that united two branches of the same community.

Just one year later, on 28 May 1914, Bena gave birth to their first child, Julius Almus Rainey, marking the beginning of a new generation in a family still carrying the weight of untold stories and unanswered questions.

From Family Lore to Front Page

The Morning It Happened

On the morning of August 12, 1915, Luther Rainey, aged about 22, was shot and killed near Groesbeck, Texas, roughly fifteen miles southeast of town. According to the newspaper report, he was struck by seven bullets—fired from both a rifle and a pistol—with three bullets passing through his body. The use of two different weapons, and the number of shots fired, spoke not to a spontaneous act, but something personal. Something deliberate.

Arrested at the scene was Ed Coker, the stepfather of Bena Rainey, née McWhorter. Deputy Sheriff Whit Popejoy took him into custody and placed him in the county jail, pending trial. The article makes no mention of motive, only that Luther had returned from West Texas the day before and had spent the night at the Coker home, where his wife and child were also staying.

That morning, Luther reportedly worked for a short time in the field. Whether this was a gesture of goodwill, an attempt to reconcile, or simply routine is unknown. But soon after, he was dead—his body riddled with bullets, his young life cut short. He left behind a widow, a child, and a storm of questions that would hover over the family for generations.

The article carefully avoids speculation. It doesn’t hint at a struggle, a quarrel, or even an argument. But what it does report—Coker’s role as both kin and killer—aligned too closely with the family lore that Bena, or perhaps her father, had killed Luther. Now, that tale had a name. A place. A date. A reality.

When Family Lore Meets Fact

This newspaper clipping, confirms what the Rainey brothers had always heard in fragments but never seen in writing: Luther Rainey was murdered, and it was indeed Bena’s stepfather, Ed Coker, who pulled the trigger.

The family secret—long treated as rural folklore passed down through innuendo and whispered warnings—wasn’t just gossip. It was truth. This wasn’t a case of mistaken identity or convoluted legend. The man whose name had disappeared from memory, whose death had been erased from formal records and family conversation, had now reemerged. And so had his killer.

Whether Bena was present, whether she knew, or whether she took part—those are questions history may never answer fully. But what is now clear is that the shadow cast over the Rainey name wasn’t fiction. It was a violent act buried just deep enough to be forgotten—until the records were pulled, the paper was found, and the trail was followed home.

Leave a comment