In the spring of 1741, a young man named John Spreadbarrow—about 19 years old—found himself confined aboard a convict transport ship, bound for the British colony of Maryland. Sentenced in Kent, England, John was just one of thousands of convicts forcibly removed from Britain and shipped across the Atlantic to serve out a period of indentured servitude in the New World. He likely landed at Annapolis, a major port for convict arrivals, where he was sold into labor to an unknown master.

How Did John Sprayberry End Up in Maryland?

John’s journey to the American colonies was not one of choice. During the 18th century, Britain used penal transportation as a way to deal with criminals, petty offenders, and even individuals who had simply fallen on hard times. Under the Transportation Act of 1718, courts sentenced convicts to seven or fourteen years of servitude in America rather than facing imprisonment or execution. The system was lucrative—merchants and ship captains profited by selling these convicts to colonial landowners in desperate need of cheap labor.

While we do not yet know the crime for which John Spreadbarrow was convicted, we do know that he appeared in Peter Wilson Coldham’s The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage, where he is listed as being sentenced in May of 1741 in Kent and subsequently transported to Maryland. Most transported convicts were not hardened criminals—many were guilty of minor theft, poaching, or other offenses tied to economic survival. For young men like John, a single misstep could mean exile to an unfamiliar land, with no guarantee of returning home.

John’s Life as an Indentured Servant

Upon arrival in Maryland, John would have been auctioned off to a landowner or tradesman, who would hold his indenture for the next seven years. Though technically not enslaved, indentured convicts had little freedom—they could be punished, worked to exhaustion, and even sold to another master. Many were put to work in tobacco fields, while others found themselves laboring in shipyards, households, or mills. With no known records of his master, it is difficult to say where John spent these years, but what is clear is that he survived.

By 1748, his indenture was completed, and he gained his freedom—a moment of transformation that marked the true beginning of his American story. Free but likely without wealth or property, John made his way south to Stafford County, Virginia, where he settled permanently. It was during this period that his surname began to evolve—whether through spelling variations, phonetic changes, or personal choice, “Spreadbarrow” became “Sprabury” and later “Sprayberry.”

The Legacy of John Sprayberry

Though John Sprayberry began his American life in forced servitude, he ultimately took control of his own destiny. His journey from a convicted man to a free settler in Virginia echoes the experience of thousands of transported convicts who helped shape colonial America. But John’s story was not just one of survival—it was one of renewal, of finding a place in a land that had once been his prison. And it was in Stafford County, Virginia, that he met Joshan Robinson, the woman who would become his wife and partner in this new chapter of life.

Joshan was the daughter of Henry Robinson and Mary Mutton, of Overwharton Parish in Stafford County. The Robinson family was part of the fabric of the growing Virginia colony, and it was within this community that John and Joshan’s paths crossed. Though the exact details of their courtship remain unknown, what we do know comes from the Register of Overwharton Parish, which recorded a significant moment in John’s life: on June 14, 1749, ‘John Sprayburry‘ and Joshan Robinson were married (The Register Of Overwharton Parish Stafford County Virginia 1723 – 1758; Harrison & King, 1961, pg. 112).

This marriage symbolized John’s full transformation from convict to citizen, from an outcast of British society to a man with roots in colonial Virginia. Now with Joshan, they established a home in Stafford County, where their growing family would mark the next chapter in their journey.

Their first child, a son named ‘James Sprabury‘, was born on June 14, 1749, bringing joy and a sense of permanence to their union. Six years later, on January 18, 1755, they welcomed another son, whom they also named ‘John Spredberry‘, further solidifying their legacy. While official records from Overwharton Parish do not document additional children, historical documents strongly suggest that John and Joshan had at least two more children—a daughter, Ann Sprayberry, and another son, Archelous Sprayberry—both likely born in Stafford County.

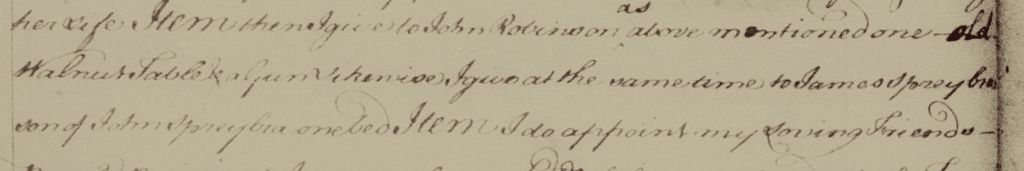

On August 3, 1753, Joshan’s father, Henry Robinson, executed his last will and testament, in which he made a specific bequest that provides critical evidence of Joshan’s identity. In his will, he stipulated, “I give at the same time to James Spreybra son of John Spreybra one bed.” While a seemingly simple inheritance, this statement holds significant genealogical value. By naming James explicitly as the son of John Spreybra [sic, Sprayberry), Henry Robinson acknowledged his grandson in a way that strongly suggests a direct familial connection.

When considered alongside the Overwharton Parish records, which document the birth of James in 1749 to John and Joshan Spreybra, Henry’s will reinforces the conclusion that Joshan was born a Robinson before her marriage. The specificity of this bequest, particularly within the context of 18th-century inheritance practices, serves as compelling proof that Joshan was Henry Robinson’s daughter. The combination of parish records and legal documentation not only solidifies her place in the Robinson family but also provides a rare and invaluable confirmation of her lineage.

John and Joshan remained in Stafford County for nearly another decade, raising their children and building a life within the familiar surroundings of Virginia’s Tidewater region. During this time, John likely worked as a farmer or tradesman, securing enough stability for his growing family. However, by the mid-1760s, the couple made a pivotal decision—to leave Stafford County behind and embark on a journey southward to Brunswick County, Virginia.

The reasons behind their move were likely influenced by the broader patterns of migration seen throughout colonial Virginia. By this time, land in the northern counties had become more expensive and scarce, pushing many families to seek new opportunities in the less densely populated southern frontier. Brunswick County, with its vast stretches of fertile land and emerging settlements, offered the promise of economic growth and independence. For John and Joshan, this move signified not just a change in location but an investment in their family’s future.

Upon arriving in Brunswick County, John and Joshan would have found a landscape both familiar and challenging. The region, though rich in agricultural potential, was still in the process of development. Settlers were clearing land, establishing homesteads, and integrating themselves into the local economy. For John, this meant adapting to a new community, acquiring land, and continuing to provide for his family in an environment that, while promising, required hard work and perseverance.

In 1764 John Sprayberry purchased a 100 acre tract of land from Simon Lane.

Brunswick County, Virginia - Deed Book 7, page 139

This Indenture made the 29th day of March in the year of our Lord Christ one thousand seven hundred and sixty four. Between Simon Lane of the County of Brunswick & Mary his wife of one part and John Sprabrough of the same county of the other part. Witnesseth that the said Simon Lane & Mary his wife for and in consideration of the sum of thrity pounds current money of Virginia to the said Simon Lane in hand paid by the said John Sprabrough at or before the ensealing and delivery of these presents [truncate] ... sell a tract or parcel of land and premises with the appurtenances sitauate lying and being in County of Brunswick being part of a tract the said Simon Lane bought of Douglas Powell but the deed of the said tract was taken out in the said Simon Lane name in year one thousand seven hundred and sixty two it being fifty yards on the north side of Jordan Road and the remainder part on the south side containing by estimation one hundred acres be the same more or less and all houses [truncate] ... In Witness whereof the said Simon Lane and Mary his wife have to by these presents set our hands and affixed our seals the day and year above written. Signed sealed & delivered in presence of Lewis Williamson, William Brewer Jr; Signed Simon Lane (his mark S) (seal), Mary Lane (her mark X) (seal)

Then a month later, John purchased a second tract from Simon Lane.

Brunswick County, Virginia - Deed Book 7, page 349

This Indenture made this twenty third day of April in the year of our Lord Christ one thousand seven hundred & sixty four. Between Simon Lane of the County of Brunswick and Mary his wife of the one part & John Spabrough of the other part. Witnesseth that the said Simon Lane & Mary his wife for and in consideration of the sum of thrity pounds current money of Virginia to the said Simon Lane in hand paid by the said Spabrourh at or before the ensealing [truncate] ... sell a tract or parcel of land and premisses with the appurtenances situate lying & being in the County of Brunswick being part of a tract belonging to the said Simon Lane lying on the Reedy Branch. Begining at a sweet gum on the Reedy Branch thence down the line to a corner red oak thence along to another corner red oak thence along the said line to the begining containing by estimation one hundred and seventy acres be the same more or less [truncate] ... In Witness whereof the said Simon Lane and Mary his wife have hereunto set their hands and affixed their seals the day and year first above written. Signed: Simon Lane (his mark S) (seal), Mary Lane (her mark X) (seal)

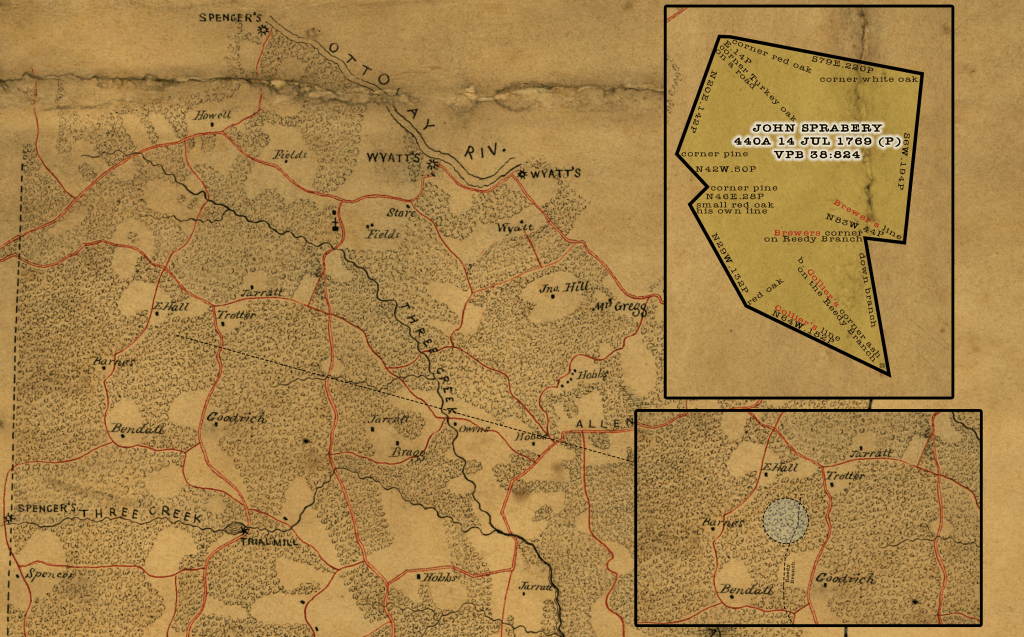

John’s journey in Brunswick County wasn’t just about settling his family—it was about securing land for their future. The property he purchased from Simon Lane was located on the south side of Reedy Branch, a small waterway that flows into Three Creek, an important tributary in the region. Today, this area sits just west of modern-day Oak Lawn in what is now Greensville County, Virginia, about ten miles northwest of Emporia.

Like many settlers of his time, John wasn’t content with just one parcel of land. As his family grew and opportunities arose, he looked to expand. In 1769, just a few years after his initial purchase, John submitted an entry for a vacant 440-acre tract that bordered his existing property. This move not only increased his landholdings but also reinforced his long-term commitment to the area. Whether for farming, business, or passing wealth down to the next generation, John was steadily building a legacy in southern Virginia.

Virginia Land Patents Book 38, pg. 824

George the Third & To all & Know ye that for divers good causes and considerations but more especially for in consideration of the sum of forty five shillings of good and lawfull money for our use paid to our Receiver General of our Revenue this our Colony and Dominion of Virginia. We have given granted and confirmed and by these presents for us our heirs and succesors; Do give grant and confirm unto John Sprabery one certain tract or parcel of land containing four hundred and forty acres lying and being in the County of Brunswick and bounded as followeth to wit; Beginning at Collin's corner ash on the Reedy branch thence by his line north sixty four degrees west one hundred and eighty two poles to a red oak thence of north twenty nine degrees west one hundred and thirty two poles to a small red oak on his own line thence by the said line north forty six degrees east twenty eight poles to a corner pine north forty two degrees west fifty poles to a corner pine north twenty degrees east one hundred forty two poles to a corner turkey oak on a road thence east fourteen poles to a corner red oak south seventy nine degrees east two hundred and twenty poles to a corner white oak south six degrees west one hundred and ninety four poles to Brewer's line thence by his line north eight three degrees west forty four poles to his corner on the Reedy branc aforesaid thence down the said branc as it meanders to the beginning. With all & To have hold & To be held & Yeilding & Paying & Provided & In witness & Witness our trusty and well beloved Norborne Baron de Botetourt our Lieutenant and Governor General of our said Colony and Dominion at Williamsburg under the seal of our said Colony the fourteenth day of July one thousand seven hundred and sixty nine. In the ninth year of our Reign.

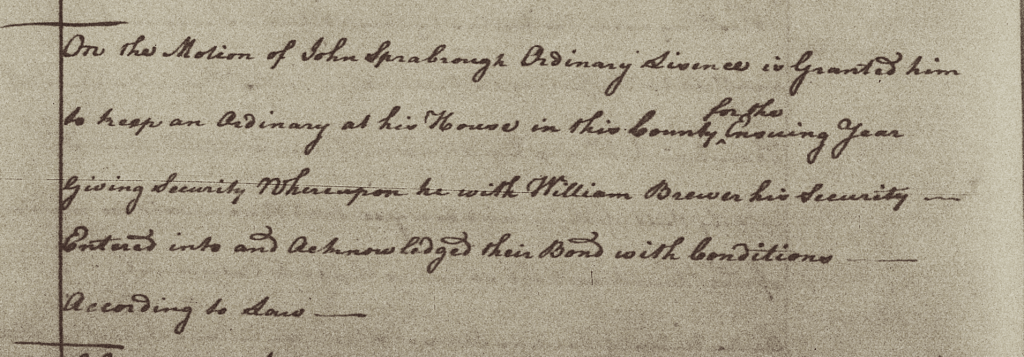

In 1765, shortly after settling his family in Brunswick County, Virginia, John petitioned the court for a license to operate an ordinary at his home—a request that was approved. Also known as a tavern or public house, an ordinary was more than just a place to eat and sleep; it was a cornerstone of colonial life. These establishments provided food, drink, and lodging for weary travelers, while also serving as lively gathering places for locals. Whether exchanging news, conducting business, or engaging in civic discussions, people from all walks of life found themselves drawn to the ordinary, making it an essential hub of both hospitality and community in 18th-century Virginia.

The location of John’s ordinary was particularly strategic. Situated in a region of Virginia north of the Meherrin River, this area functioned as a transient corridor for traders and settlers journeying between Virginia and North Carolina, as well as points further south. The ordinary would have provided essential services to these travelers, offering rest and sustenance during their journeys. Additionally, it would have served as a local gathering place, fostering community bonds and facilitating the exchange of information among residents.

Recognizing the importance and success of his establishment, John renewed his ordinary license in 1768 (Ibid, Book 11, pg. 42), ensuring the continued operation of this community cornerstone. Colonial Virginia law required ordinary keepers to obtain licenses, which were regulated to maintain order and set standard rates for services.

In 1774, John Sprayberry executed his last will and testament:

Brunswick County, Virginia Will Book 4, pg. 218

In the name of God Amen, I John Sprabrouough of Brunswick County in the Colony of Virginia being very sick & weak in body but of sound mind & memory thanks be unto belong to God for the same do this the tenth day of July in the year of our Lord Christ one thousand seven hundred and seventy four make and ordain this my last will and testament in manner and form as following;

Item I lend to my loving wife Joshen Spraborough all my movable estate that I do not give to my two sons James and John during her life and at her decease to go to my son Archelus Spraborough.

Item I give and bequeath unto my loving son James Spraborough the plantation where on he now lives with one hundred & seventy five acres joining there to also one cow and calf one leather bed and furniture that he has in his possession to him and his heirs forever.

Item I give and bequeath unto my loving son John Spraborough the remaining part of the tract of land that my son James lives on which will be one hundred and seventy five acres after my son Archelous Spraborough has fifty acres out of the tract also one cow and calf and one feather bed and furniture to hm and his heirs forever.

Item I give and desire that one hundred and forty acres of my land Beginning at a corner red oak running along Battses line to Joshua Dewberry's line thence to Brewers corner tree to be sold and the money from land to my wife as above mentioned.

Item I give and bequeath to my loving daughter Ann Spraborough one cow and calf and one feather bed and furniture to her and her heirs forever.

Item I do hereby my loving wife relict and sole Executor of this my last will and testament as witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal this day and year first above written.

Signed Sealed and Delivered in presence of Rubin Addams, William Garner

Signed: John Spraborough (seal)

At a court held for Brunswick Conty the 26 day September 1774. This will was proved according to law by the oaths of Rubin Addams and William Garner the witnesses thereunto and orders to be recorded and on the petition of Joshen Spraborrough the Executrix therein named who who made oath thereto & Together with John Spraborrough and William Garner her securities entered into and acknowledged their bond in the penalty of five hundred pounds [---] as the law directs. Certificate was granted her for having a probate there of in due form.

For more than fifteen years, the Sprayberry family made their home along Reedy Branch, building their lives in Brunswick County. Their presence in the area is well-documented, with Joshan Sprayberry last appearing in the county records in February 1778. That year, she was noted in Brunswick County Order Book 13 for a land transaction between her with son, James Sprayberry, and William Garner the previous January. Beyond this record, no further evidence has surfaced to indicate when she may have passed away, leaving the details of her later years and death a mystery.

As time went on, the next generation of Sprayberry men—James, John, and Archelous (Archer)—began carving out their own paths. While they remained tied to the Reedy Branch community, they also ventured beyond it. James Sprayberry briefly relocated to Wayne County, North Carolina, in the early 1780s, though he ultimately returned home.

By the early 1790s, change was once again on the horizon. James and John Sprayberry left Brunswick County behind and migrated further south to Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, seeking new opportunities. Meanwhile, Archelous Sprayberry remained, as confirmed by local tax records.

Though the Sprayberry family eventually moved beyond Reedy Branch, their legacy in Brunswick County, Virginia, was well established. From John’s early days as an ordinary keeper to the land transactions and migrations of his sons, their story is one of resilience, movement, and change—hallmarks of so many early American families. While questions remain, especially regarding Joshan’s later years, their presence in the historical record serves as a lasting reminder of the family’s place in Virginia’s colonial past.

Leave a comment