Emerging from the Chester-New Castle Cooridor in the early 1700’s, the Cole family’s legacy is stitched together through scattered historical documents, that tell the story of a family that were early pioneers along the developing Great Wagon Road, becoming early settlers and planting seeds of growth across the vast expanse of colonial America.

As the Great Wagon Road wove deeper into the frontier, the Cole brothers—James, John, and Mark— along with James’ in-laws, the Renfros, first appear in 1736 near Opequon Creek in the Shenandoah Valley, near present-day Winchester, Virginia.

From this first settlement, the Coles stitched their presence further into the fabric of colonial America, appearing in records over the next two decades in Frederick, Augusta, Lunenburg, and Bedford counties, leaving their mark on communities sprouting along and near the Great Wagon Road.

While James, John, and Mark pushed the Cole family’s legacy along the Great Wagon Road, their brothers Stephen and William along with their sister Elizabeth, remained rooted in Pennsylvania. Stephen established himself as a respected butcher in the borough of Chester within Chester Township, while William set down roots in the pastoral lands of West Nottingham Township. Elizabeth married Thomas Wilcox, settling in Concord Township, where they built one of colonial America’s first paper mills, the renowned Ivy Mills.

Stephen Cole’s life, however, took a tragic turn when he passed away in 1744, leaving behind his widow Martha and six young children: John, James, Elizabeth, Stephen Jr., William, and Mark Cole.

Chester’s Legacy Meets Virginia’s Promise:

The Cole Family Migration

Though records remain fragmented, they provide intriguing clues about the movements of Stephen Cole’s sons after his death. Some of his sons—John, Stephen Jr., William, and Mark—appear to have left Chester, Pennsylvania, and ventured to and south on the Great Wagon Road to join their uncles James and Mark Cole in Lunenburg County, Virginia, as the area transitioned into Bedford County.

Meanwhile, James Cole, another of Stephen’s sons, is believed to have stayed in Pennsylvania, residing in the area between Ridley, Middletown and Aston Townships (these townships surrounded Chester).

It is speculated that John Cole was living in Lunenburg County by the time it became Bedford County and that he married Jane Bounds around 1753. Jane was the daughter of James Bounds, who lived in Frederick County, Virginia, during the 1740s. James Bounds had ties to other notable families, such as the Renfros. In August 1744, Frederick County court records show James Bounds, William Renfroe, and others were ordered to supply male labor for roadwork under McKay’s oversight, connecting the mouth of Crooked Run to Capt. John Hite’s (Frederick Order Book 1, pg. 170, 177). By 1753, James Bounds had moved to Bedford County, where he was appointed constable in November 1754 (Bedford Order Book 1A, pg. 41).

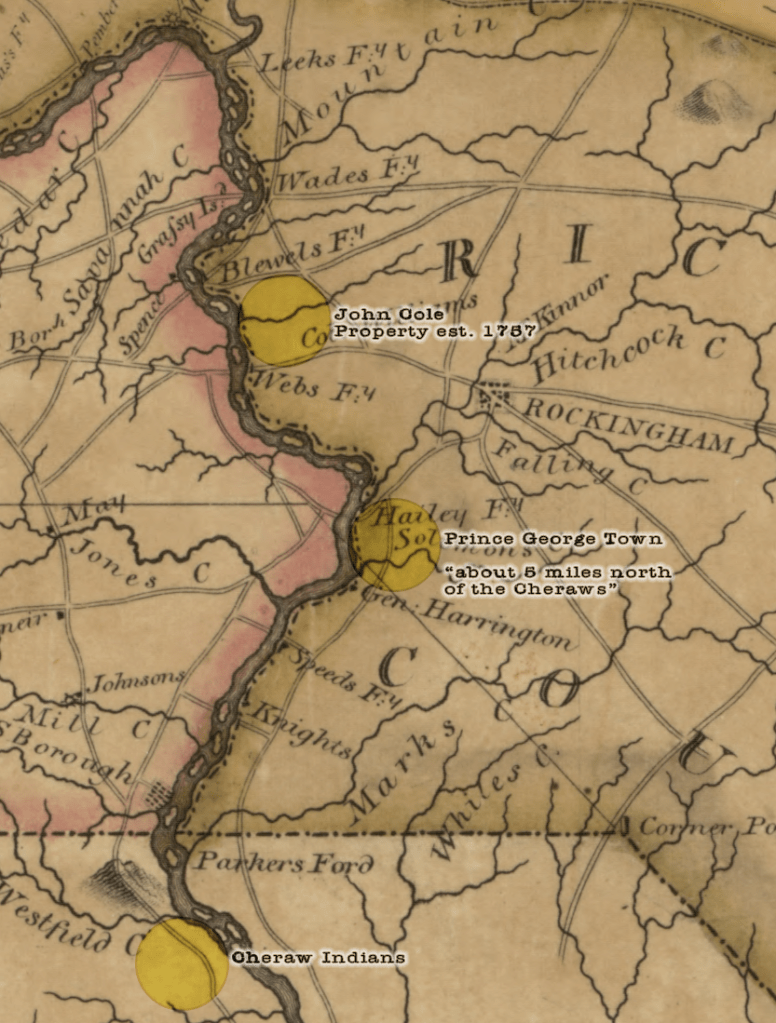

From Bedford County, the Cole brothers—John, Stephen Jr, Mark, and William—began to establish roots further south during the mid-18th century, spreading across key locations in colonial North Carolina. The family chose strategic settlements near Salisbury in Rowan County and Prince George Town in Anson County. These locations, connected by the Yadkin and Pee Dee Rivers, were well-suited for their occupations and growing ambitions. Salisbury, with its diverse and growing economy, provided a hub for skilled labor and trade, while Prince George Town offered an emerging market along the Pee Dee River, albeit less established. Together, these two locations provided the brothers with a foundation for both their personal trades and a burgeoning family trading operation.

John Cole, a shoemaker, was among the first to establish a presence in Anson County, purchasing 400 acres on Cartledge Creek on December 31, 1757. In 1760, he sold 100 acres of this tract to his brother Stephen, a hatter, demonstrating an early example of familial collaboration. This deed was witnessed by their brother William Cole, a cordwainer, and a local associate, William Coleman. By 1761, both John and Stephen had purchased half-acre lots in Prince George Town, adjacent to one another. Prince George Town (established in 1759) was a few miles away from his Cartledge Creek property. John and Stephen were listed as merchants, with John styled as a “Merchant of Anson County” and Stephen as a “Merchant of Bladen County,” suggesting that the brothers were leveraging their trades to engage in a localized trading network that likely extended north to their base in Salisbury, Rowan County.

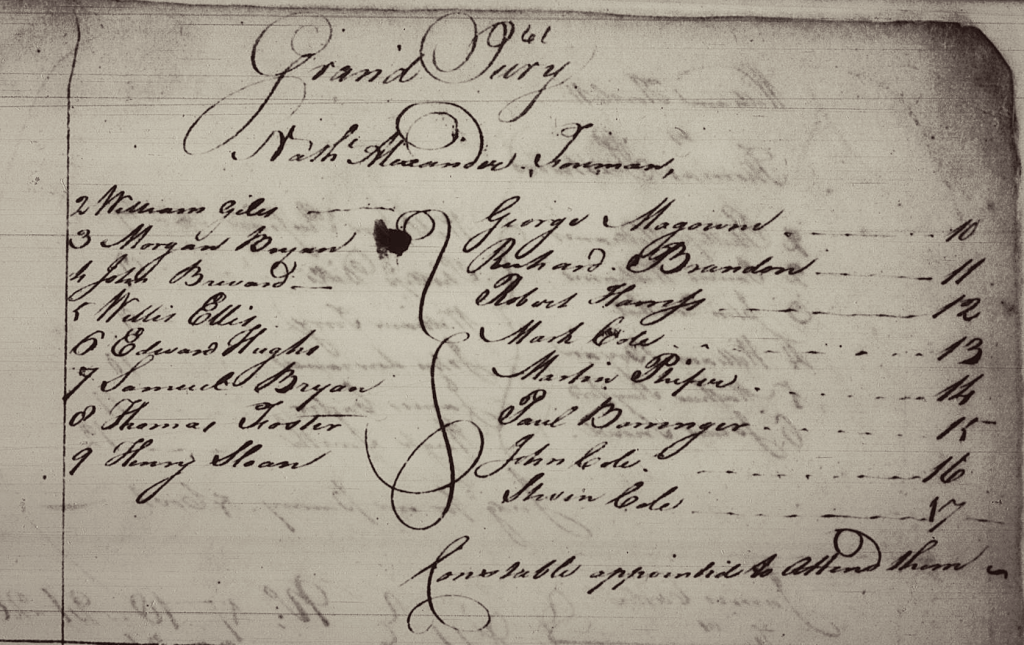

Salisbury further connects the brothers’ activities, as records from 1762 show John, Stephen, and Mark serving as grand jurors in the Salisbury Supreme Court. This presence highlights their ties to Rowan County, where they presumably had outlets for their goods. Evidence suggests they likely resided near the Jersey Settlement and Tract #9 of Henry McCulloch’s property, which was on the north side of Yadkin River and west of Swearing Creek. This geographic positioning allowed them to capitalize on the economic opportunities along the interconnected waterways and The Trading Ford.

The Trading Ford was a historically significant crossing point on the Yadkin River, located on the south side across of the Jersey Settlement. The natural shallow crossing was used by Native Americans, early settlers, and travelers during colonial times and beyond. Its strategic location made it an important landmark for commerce, migration, and military activity. It connected key routes, including the Great Wagon Road and the earlier Trading Path, also known as the Western Path, which extended from the northeast into the region. This historic route played a vital role in facilitating trade with the Cherokee and Catawba Indians, serving as a lifeline for commerce and cultural exchange long before and during early colonial settlement.

The 22 March 1762 Salisbury Supreme Court record that conviened a Grand Jury. The jury was made of Nathaniel Alexander – Foreman, William Giles, Morgan Bryan, John Brevard [sic], Willis Ellis, Edward Hughes, Samuel Bryan, Thomas Foster, Henry Sloan, George Magown [sic], Richard Brandon, Robert Harris, Mark Cole, Martin Phiser [sic], Paul Bassinger, John Cole and Steven Cole (Stephen Cole).

From this list, Edward Hughes played a significant role as a trustee tasked with securing a grant of forty acres from Lord Granville’s land office for the construction of Salisbury’s public buildings, highlighting his importance in the community’s early development. Meanwhile, William Giles, Willis Ellis, and Henry Sloan were notable landowners within the boundaries of Tract #9 of the McCulloch Grant, a key area in Rowan County’s settlement history.

By April of 1763, Mark Cole appears to have moved to Anson County. In 1763, Mark Cole, along with Charles Robinson and Thomas Ellerby all of Anson County, entered into a £50 bond to operate a tavern (Rowan, Public Records 1756-1940, (pg. 210 of 400)). This bond, recorded in Rowan County’s Salisbury court, served as a guarantee of their compliance with colonial tavern regulations. Taverns were central to community life, and such bonds ensured order and accountability in these establishments.

The Rowan County court minutes from July 1766 include an exciting detail about William Cole:

“Ordered that William Cole be appointed overseer of the Uwary Road in the room of Williams, who has left this province, and for his former District.” (Rowan Court Minutes 1753-1772, pg. 629).

This record not only places William Cole in Rowan County during the 1760s but also hints at his responsibilities in maintaining the important Uwary Road. Preliminary research suggests the road likely connected Henry McCulloch’s lands near the Yadkin River to the west, leading toward the Uwharrie River.

This court order cements William Cole’s presence in Rowan County and offers an intriguing glimpse into his role in shaping the local infrastructure.

William Cole in 1768, purchased two enslaved individuals from his uncle Mark Cole (Rowan DB 14:658), who migrated from Bedford County, Virginia and settled in Craven County, South Carolina in the late 1750s . The deed explicitly states, “Mark Cole of Craven County, South Carolina, and in Saint Mark’s Parish hath bargained, sold and delivered unto William Cole of Rowan County and province of North Carolina.” This transaction underscores the relationship between the two branches, as well as their economic and legal interactions across state lines. Notably, Mark Cole Sr is believed to have died around 1769 in Craven County. By this time, South Carolina had transitioned from a county system to a district system, with Craven County becoming extinct and now called Camden District. If the deed were initiated after 1769, it would likely have referred to the Camden District or the smaller Clarendon or Claremont Counties established in 1785.

Further complicating the timeline is a record found in the Rowan County Court Minutes (1793–1800), pg. 269, which lists the transaction as occurring in 1788. This entry appears in an “Inventory of Slave Conveyances,” providing a formal record of the sale. However, given the language and details in the original deed, the 1768 date is more likely to be accurate. This discrepancy highlights the challenges genealogists face when reconciling differing dates and interpretations in historical records. Regardless, this deed, along with the court record, provides valuable evidence of a interaction between the Rowan and Craven branches of the Cole family, offering insights into their shared history and connections.

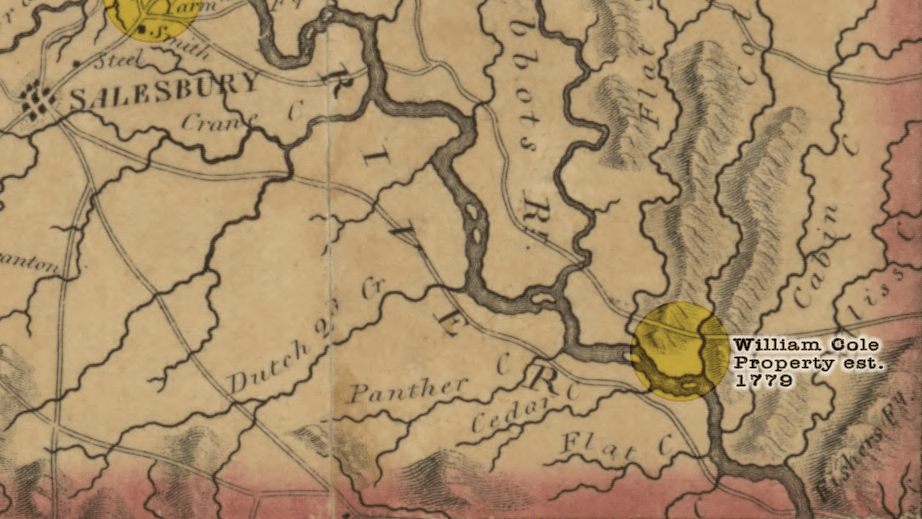

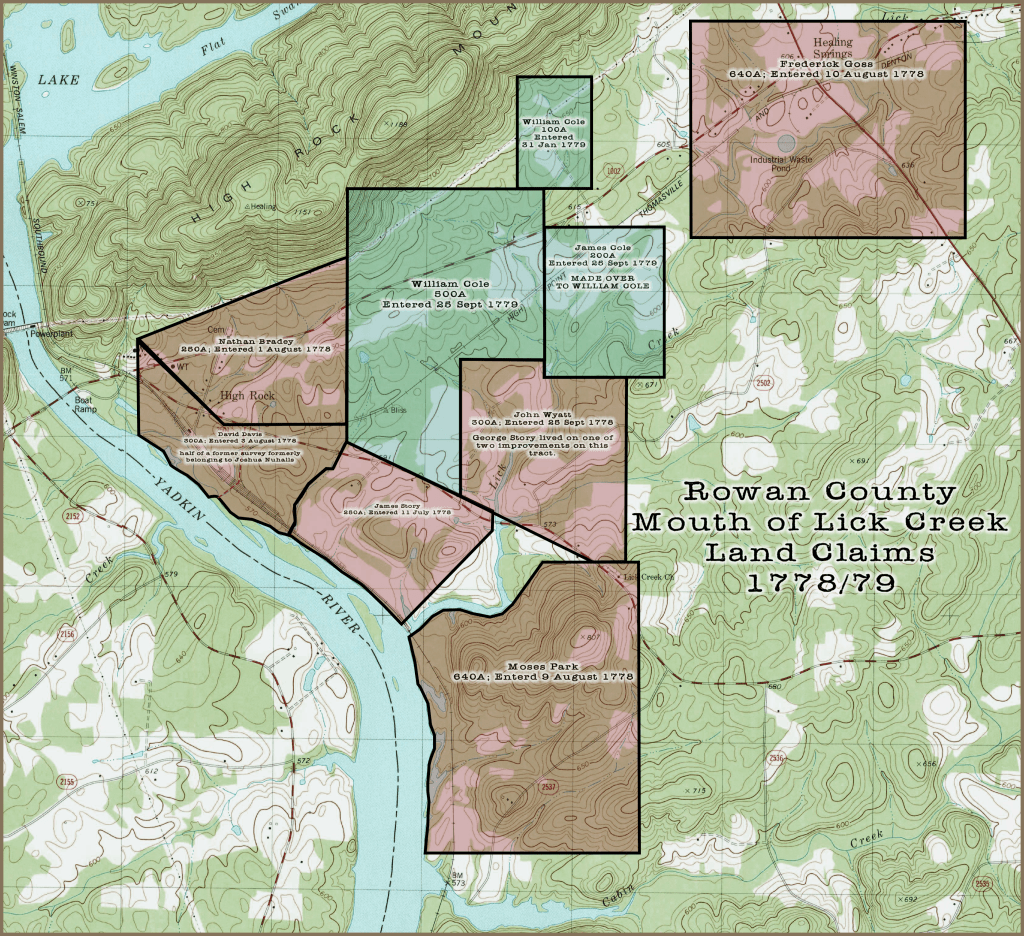

By 1778, William Cole likely found himself navigating the rugged terrain near the Yadkin River and Lick Creek, scouting for vacant land that could become his new homestead. These explorations were a critical first step in the settlement process, as finding a fertile and resource-rich tract was essential for building a successful future.

In January of the following year, WIlliam made his way to Salisbury to take the next step in securing his claim. There, he met with the Entry Taker and provided a detailed description of the desired tract, including its boundaries and notable features. His claim was recorded on 31 January, 1779, and read: “William Cole enters 100 acres of land in Rowan County on the waters of Lick Creek on the southeast side of Flatt Swamp Mountain, known by the name of the Mulberry Bottoms.”

That September, William expanded his claim, filing for an additional 500 acres adjoining his original claim. The official entry indicated that this 500 acres layed on the northwest side of Lick Creek, between Lick Creek and the Flat Swamp Mountain adjoining James Coles entry.

This James Cole (either a cousin from the Cole kin in Bedford or Halifax Counties in Virginia or the remote possibility that this James Cole could be his older brother that may have migrated from Pennsylvania).

The land records indicated that James Cole made this entry over to William Cole. This notation was a formal way of recording the reassignment of rights to the land. Once the claim was “made over” to William, he would have the responsibility to follow through with the warrant issuance, survey, and eventual patenting process to secure full owner ship of the land.

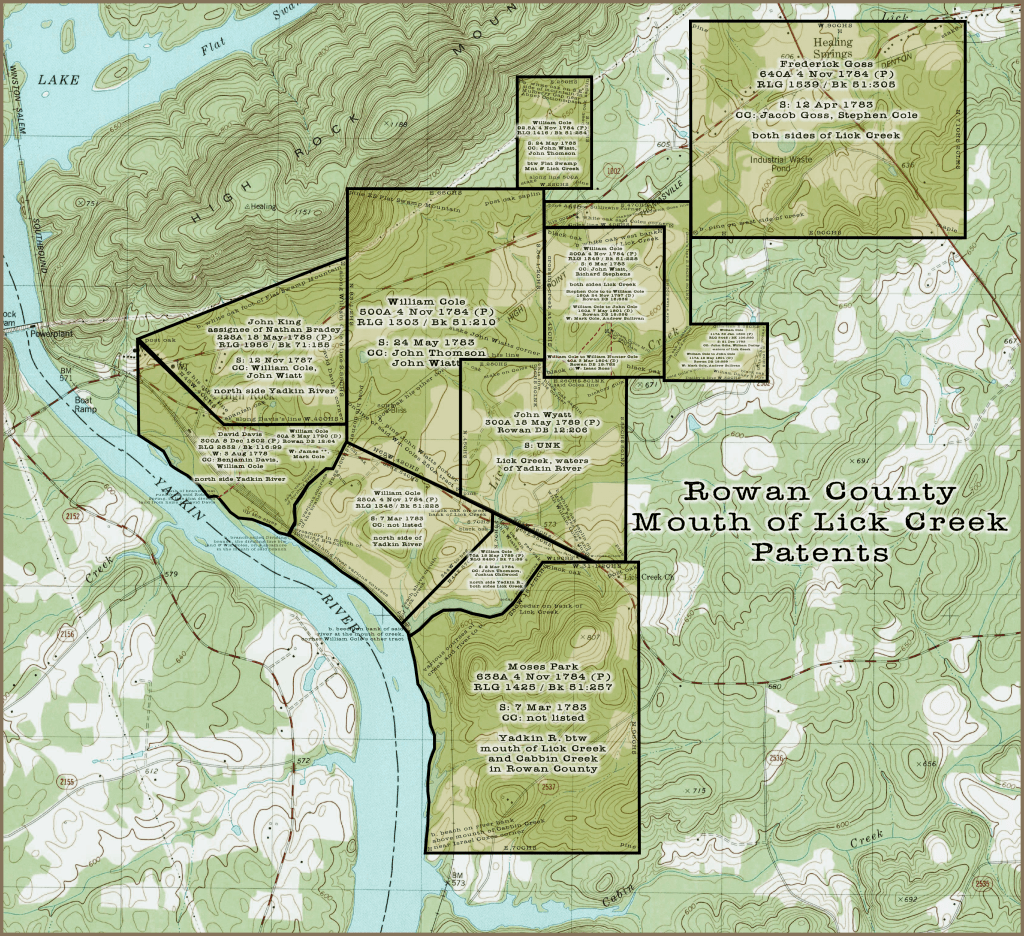

Over the following decades, William Cole expanded his foothold in the region, securing additional land patents that solidified his place as a prominent landowner near the mouth of Lick Creek. His growing estate became a landmark of the area and he as a figure in the development of this thriving fontier region.

Over the next several decades, William Cole would secure additional patents around the mouth of Lick Creek.

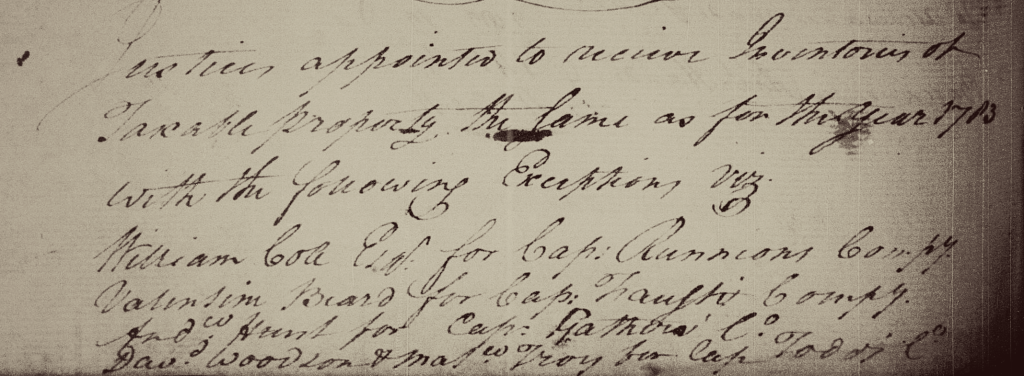

In 1783, William Cole, Esq., was appointed to oversee the collection of taxable property inventories in Rowan County, specifically within the jurisdiction of Captain Phineas Runyon’s company. In his capacity as a respected community figure and landowner, William Cole would have been entrusted with gathering detailed inventories of taxable property. These inventories included land acreage, livestock, agricultural yields, and other assets that contributed to the settler’s wealth.

As an “Esq.” (Esquire), a title denoting his social standing and likely administrative authority, William acted as a trusted intermediary between the settlers and higher county officials. This role required not only an understanding of local property holdings but also the ability to resolve disputes, accurately document claims, and forward the completed inventories to Rowan County officials.

Captain Phineas Runyon’s company likely served as both a militia district doubling as a civic administrative area, setting the geographical boundaries for the taxation process in Rowan County. This district stretched from the Yadkin River eastward, covering the areas along Lick Creek and Cabbin Creek. Captain Runyon owned a tract of land at the head of Cabbin Creek, located on the opposite side of the district from where William Cole lived. Phineas Runyon also owned property near the head of Lick Creek, adjoining the land of Absalom Cameron, who would later become part of the Cole family when he married William Cole’s daughter, Mary Cole, in 1786.

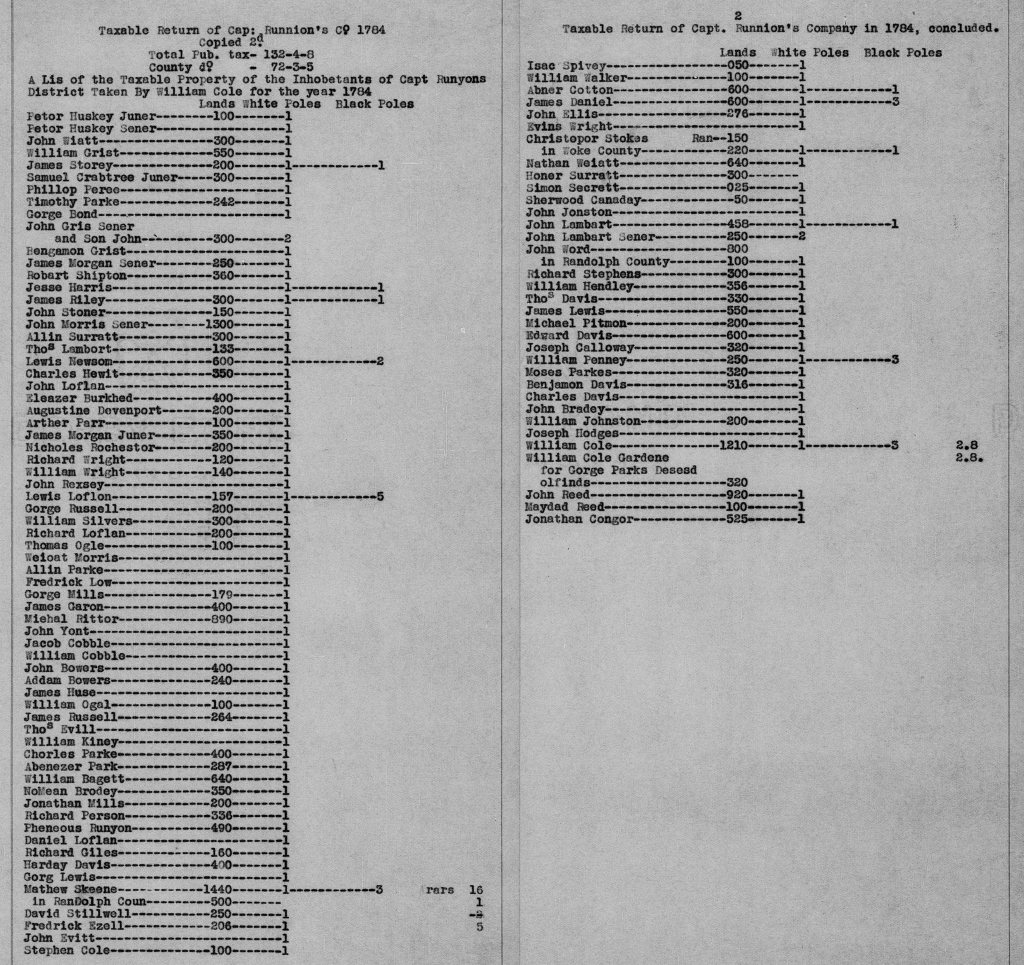

The 1784 tax list, collected by William Cole, offers a fascinating glimpse into the residents of this valley south of Flat Swamp Mountain. Through these records, we gain valuable insight into the lives of the families who called this region home and the community that William helped document and serve.

On 5 May 1784, the Rowan Inferier Court appointed William Cole Esqr. as the guardian for John Park, Mary Park, Agness Park, Joshua Park, Huldy Park and Jacob Nichols Park, orphans of George Park deceased. William Cole gave bond with James McKay as security in £400 (Rowan Court Records 1773-1786, pg. 413).

The search for William Cole’s wife continues to intrigue this research. It seems plausible to imagine that she could have come from one of the families of The Jersey Settlement, Tract #9, or the Salisbury area. From around 1764 to 1785, William and his wife had the following children:

- Martha Cole – b. 22 September 1764; d. 17 October 1822, Rowan County, North Carolina (Davidson Co. formed 9 December 1822); m. David Cox, 5 April 1788

- Mary Cole – b. ca 1766; d. ca 1821, Rowan County, North Carolina; m. Absalom Cameron, 20 February 1786

- Stephen Cole – b. ca 1768; d. ca August 1841, Lincoln County, Tennessee; m. Elizabeth Conger, 27 October 1789

- Mark Cole – b. ca 1772, d. ; m. Sarah Cameron, 18 Jun 1794

- Ellis Cole, b. ca 1774; d. ca 1801/02, Rowan County, North Carolina; m. James Smith, 2 October 1792

- Betsy Cole, b. ca 1778, Rowan County, North Carolina; d.; m. Daniel Hunt, 10 May 1798

- John Cole – b., Rowan County, North Carolina;

- James Cole – b., Rowan County, North Carolina; m. Elizabeth Daniel, 30 September 1803

- William Hunter Cole – b., Rowan County

- Elizabeth Cole – b. 1781, Rowan County, North Carolina; d. April 1870, Davidson County, North Carolina; m. John Feezor, 15 August 1800

William Cole’s life story reflects the journey of a pioneering spirit who left his mark on the communities he called home. Born around 1738 in Chester Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania, William was the son of Stephen and Martha Hunter Cole, part of a family that would go on to play significant roles in the early settlement of colonial America. From his beginnings in Pennsylvania to his life in Rowan County, North Carolina, William was part of a generation that expanded into new territories, planting roots that would grow for generations.

William’s presumed passing in the fall of 1808 marked the end of an era for the Cole family in Rowan County. While the exact date of his death is not documented, several clues provide a timeline. In 1809, the Rowan County tax list for Captain Ratts’ or Captain William Bean’s district does not include William’s name, though his son James is listed. Typically, tax lists were compiled early in the year, between January and March, and finalized after collection by May or June. Given that William appeared on earlier tax lists but not on the 1809 list, it is likely he passed away after the 1808 tax collection but before the next year’s compilation—suggesting a death in the latter months of 1808. On August 12, 1809, the Rowan courts granted letters of administration for his estate to John Fuzor, with David Cox and James Smith providing a bond of £600 (Rowan Court Minutes 1807-1813, pg. 141), officially marking the end of William’s life and the beginning of his estate’s settlement.

Leave a comment