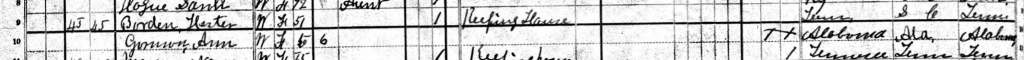

The first documented appearance of Annie Garmon in historical records is in the 1880 U.S. Federal Census, which covers the Borden Springs area of Cleburne County, Alabama. In this record, she is listed as “Ann Gormon”, aged 6 years old, with a birthdate of June 1874 and born in Alabama. The census further notes that both her mother and father were also born in Alabama, though their identities remain unknown. This census provides the earliest evidence of Annie’s presence and hints at her Alabama roots.

Annie is recorded as living in the household of Hester Putnam Borden, suggesting a potential close familial relationship. Hester Putnam Borden, the head of the household, was born on 30 June 1828 in Tennessee. While the census does not clarify the exact relationship between Annie and Hester, it is likely that Annie was under Hester’s care due to family ties. The absence of Annie’s parents in the household could indicate that they were deceased or otherwise unable to care for her, a common situation that often resulted in extended family members assuming responsibility for young relatives.

Hester Putnam Borden, as the daughter of Hiram Putnam and Loamy Mercer, came from a family that migrated from Union County, South Carolina to Tennessee, Kentucky, and then Alabama. By 1850, Hiram Putnam had settled in Benton County, Alabama (later renamed Calhoun County) where he passed away in 1856. This genealogical background places Hester in a family network that could have included Annie’s mother. While the census provides no further details about Annie’s lineage, her presence in Hester’s household is a significant clue for tracing her origins.

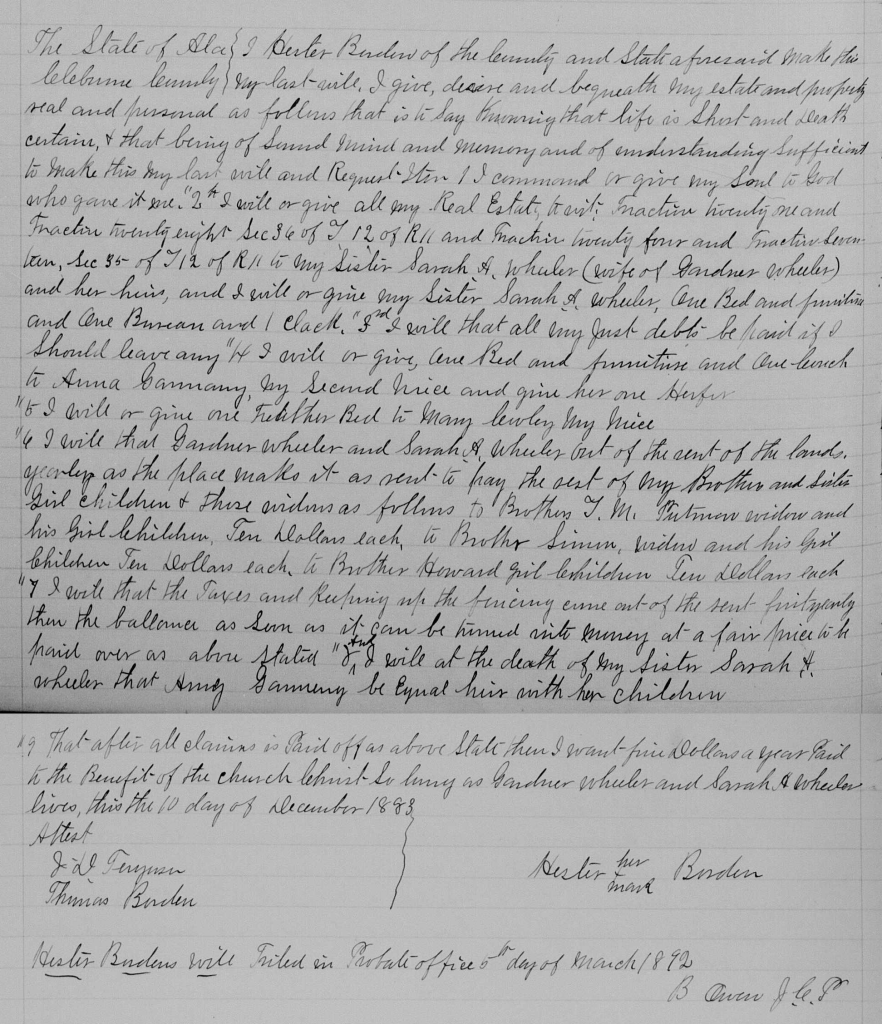

Just three years after the 1880 census, Hester created her last will and testament on 10 December 1883. This document would confirm her special regard for Annie, naming her as a significant heir and highlighting her unique position in the family network.

Heflin, Cleburne County, Alabama, Wills and Inventorys Volume 2, pg. 126

The State of Alabama, Cleburne County

I Hester Borden of the county and state foresaid make this my last will. I give, desire and bequeath my estate and property real and personal as follows, that is to say knowing that life is short and death certain, & that being of sound mind and memory and of understanding sufficient to make this my last will and request;

Item 1, I command or give my soul to God who gave it me.

2th I will or give all my real estate to wit: Fraction twenty one and fraction twenty eight Sec 36 of T12 of R11 and Fraction twenty four and Fraction seventeen, sec 35 of T12 of R11 to my sister Sarah A Wheeler (wife of Gardner Wheeler) and her heirs and I will or give my sister Sarah A Wheeler one bed and furniture and one burean and 1 clock.

3rd I will that all my just debts be paid if I should leave any.

4 I will or give one bed and furniture and one bench to Anna Garmany, my second niece and give her one hefer.

5 I will or give one feather bed to Mary Cooley my niece

6 I will that Gardner Wheeler and Sarah A Wheeler out of the rent of the lands yearlong as the place make it as rent to pay the rest of my brothers and sisters girl children & those widows as follows to brothers T.M. Putman widow and his girl children ten dollars each, to brother Simon widow and his girl children ten dollars each, to brother Howard girl children ten dollars each.

7 I will that the taxes and keeping of the fencing came out of the rent first yearly then the ballance as soon as it can be turned into money at a fair price to be paid over as above stated.

8 I will at the death of my sister Sarah A Wheeler that Anny Garmeny be equal heir with her children.

9. That after all claims is paid off as above state then I want five dollars a year paid to the benefit of the Church Christ so long as Gardner Wheeler and Sarah A Wheeler lives this the 10 day of December 1883.

Attest J.D. Ferguson, Thomas Borden

Signed: Hester (her mark) Borden

Hester Bordens will filed in Probate Office 5 day of March 1892

Hester Putnam Borden’s will shows us that ‘Anna Garmany‘ or Annie Garmon is explicitly identified as Hester’s second niece, which implies that Annie is thought to be the daughter of one of Hester’s nieces. This relationship places Annie as a member of the extended family, likely descended from one of Hester’s brothers or sisters. The designation “second niece” suggest that Annie is at least one generation removed from Hester, which aligns with the genealogical convention of describing a great-niece. Additionally, Annie’s presence in the will as a beneficiary alongside Hester’s closer relatives, such as her sister Sarah A. Putnam Wheeler and her nieces, demonstrates a familial bond and Hester’s regard for Annie.

‘Anna Garmany‘ is bequeathed practical and modest items: one bed, furniture, a bench, and a heifer, indicating that she may have been relatively young and still establishing herself at the time of Hester’s death. The inclusion of livestock (a heifer) suggests Hester intended to provide Annie with a means of economic support, which would normally point to Annie being unmarried or not yet fully independent.

Hester’s inclusion of Item 8 in her will, specifying that ‘Annie Garmany’ would become an equal heir with Sarah Wheeler’s children upon Sarah’s death, reveals Hester’s strong commitment to securing Annie’s future. By ensuring that Annie would inherit equally with Sarah’s biological children, Hester demonstrated her intent to safeguard Annie’s financial security and solidify her place within the family. This provision suggests that Annie may have been in a vulnerable position—possibly orphaned or without direct inheritance from her own parents—and that Hester saw it as her responsibility to protect Annie’s well-being beyond her lifetime.

Although the will does not explicitly identify Annie’s parents, it provides strong clues for further research. Since Annie is identified as Hester’s second niece, her parents are likely among the nieces or “girl children” mentioned in the will. Hester explicitly names her brothers T.M. Putman (Thomas), Simon Putman, and Howard Putman and references their daughters (her nieces). Anna may be one of the “girl children” connected to these brothers or potentially a daughter of an unnamed niece from one of Hester’s sisters.

The Search Narrows: Promising Leads on Annie Garmon’s Lineage

Annie Garmon’s granddaughter, Irene Sprayberry, recorded in her family Bible that her grandmother’s last name was Garmany. While some might initially dismiss this as a potential mistake, the evidence strongly supports Irene’s accuracy. Hester Borden’s will specifically identifies Annie’s last name as Garmany, aligning with Irene’s family record. This corroboration makes it far more likely that Garmany is correct and not a misinterpretation or misrecording. Any variation, such as “Garmon” seen in the 1880 census, may simply reflect the common errors or inconsistencies often found in census records of the time. Together, these pieces of evidence strongly validate that Garmany is Annie’s proper last name.

The surname Garmon or Garmany does not appear to have been present in the immediate Borden Springs area of Alabama. However, there was a Garmany family that owned property about seven miles south of Borden Springs in Fruithurst, Alabama, and there were also some Garmon families located near Hokes Bluff on the way to Gadsden. While these clues are intriguing, there currently isn’t enough information to confidently determine who Anna Garmany’s father may have been. Further research into these families might eventually reveal a connection.

Shifting focus to researching potential leads for identifying Annie’s mother may prove more fruitful. By exploring maternal connections, we might uncover records or family ties that provide clearer insights into Annie’s lineage. This approach could reveal new information maternal family members, or other documents that shed light on her mother’s identity and, in turn, help piece together the puzzle of Annie’s ancestry.

In 1850, Hester Putnam was living at home with her parents and siblings: Leonidas Putnam, Howard Putnam, and Sarah A. Wheeler. Her brother Thomas Putnam was married and living next door, while her eldest sister, Phoebe Putnam Ruff, was also married and living nearby, all in the Palestine, Alabama area. The close proximity of the family highlights their tight-knit community and connections during this time.

By 1866, notable names still residing in the Palestine area included Howard Putnam, J.S. Borden, Gardner Wheeler, Louanna Putnam, Louidus [sic] Putnam, and J.R. Ruff (1866 Alabama Census). These individuals reflect the continuing presence of Hester’s family and extended kin in the region.

Among these names, Howard Putnam and Leonidas Putnam (Louidus) were Hester Putnam Borden’s brothers. Gardner Wheeler (husband of Sarah A. Putnam) and J.R. Ruff (Jefferson Ruff, husband of Phoebe Putnam Ruff) were her brothers-in-law. J.S. Borden (John) was related to Hester’s husband, John Borden, while Louanna Putnam is believed to be Loamy Mercer Putnam, Hester’s mother. The connections among these individuals illustrate the familial bonds and relationships that shaped Hester’s life in Alabama.

By 1870, Phoebe Putnam Ruff is listed in the U.S. Census, living without her husband, suggesting she may have been widowed. Her household, located just a few doors away from her sister, Sarah A. Putnam Wheeler, includes her daughters: Arena (Luverna Ruff), age 25; Hettie (Louisa F. Ruff, also known as Hester Ruff), age 21; and Martha, age 18. Her oldest daughter, Nancy Ann Ruff, was married and living with her husband, Thomas Buchanan, in nearby Cherokee County. Nancy Ann’s household included their daughters, Martha and Anne (Sarah). Meanwhile, Phoebe’s other two daughters, Rebecca and Rachael, are not accounted for in 1870, though both would have been over the age of 18 by this time. Rebecca Ruff would end up marring Edward Doig and was living in Cleburne County in 1892. She appears to have had one daughter and died before 1900. Rachael Ruff may have died before 1892 as she is not listed as a child of Phoebe Ruff in Hester Bordens probate records.

No additional records for Phoebe Putnam Ruff have been found after the 1870 census. Current research suggests that she likely passed away before 1875, though further documentation is needed to confirm her exact date and circumstances of death. This gap in records underscores the challenges of tracing individuals during this period, particularly for women whose lives were less frequently documented.

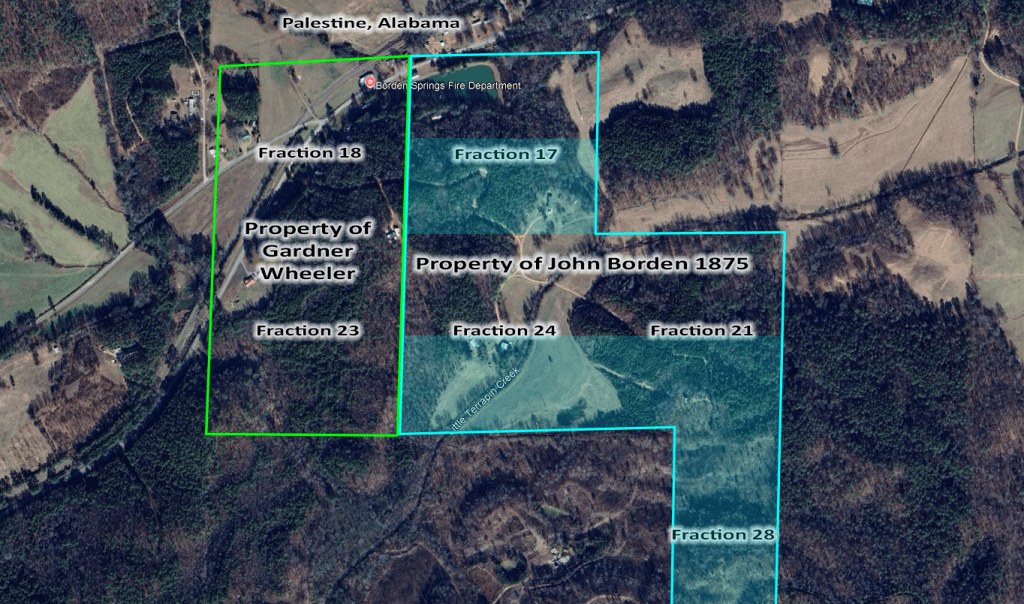

In 1875, Hester’s husband John Borden died and amongst his numerous land holdings, were several properties in the Palestine area (John and Hester lived a few miles away in Borden Springs)(Cleburne. Probate Estate Case Files 1875-1913, digital page 26 of 1,284):

- Fraction 17 in Section 35 of Township 12 South Range 11 East

- Fraction 24 in Section 35 of Township 12 South Range 11 East

- Fraction 21 in Section 36 of Township 12 South Range 11 East

- East Part of Fraction 28 Section 36 of Township 12 South Range 11 East

In October of 1875, Hester Borden received as part of her share from the John Borden estate, the south end of Fraction 17, 24, 21 and the east side of Fraction 28 (areas hightlighted in blue)(Cleburne. Probate Estate Case Files 1875-1913, digital page 53 of 1,284).

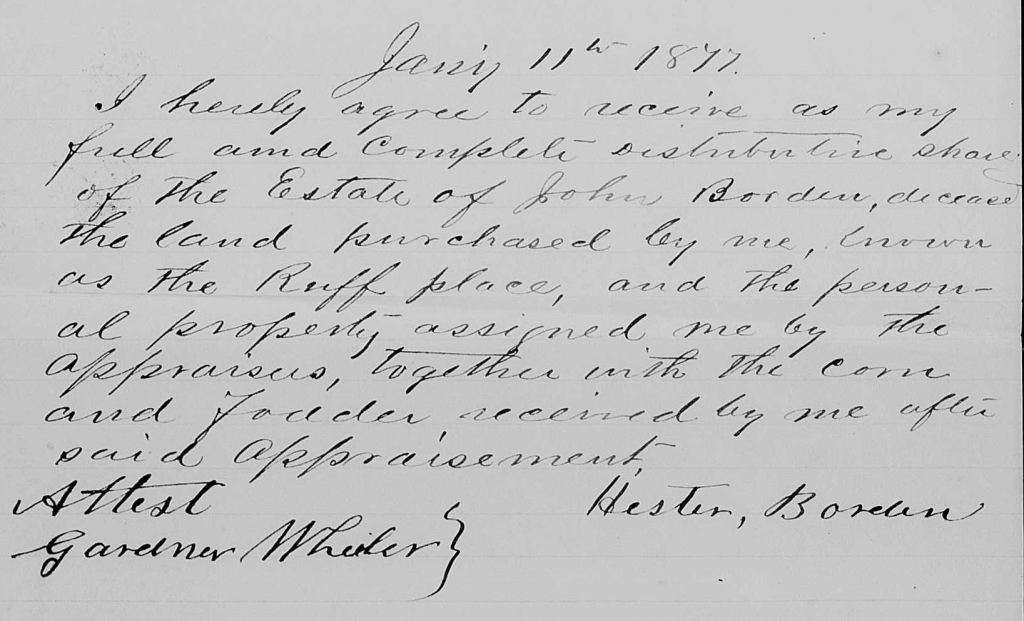

She also purchased a tract of land from the estate known as the Ruff Place (Cleburne Probate Estate Case Files, 1875-1913, digital page 119 of 1,284). Based on census records and other evidence, the Ruff Place is believed to have been the property where Jefferson and Phoebe Ruff lived. This land was located in Section 36, near or adjoining the property that later came into the ownership of Hester Borden.

It is believed that since the John Borden estate appears to have owned the Ruff Place, Phoebe Ruff may have passed away (circa 1872-73), prompting John and Hester Borden to purchase the property. This acquisition could have been motivated by opportunity or by a desire to provide a means of support for Phoebe’s daughters, who would have been left without parents after Jefferson and Phoebe’s deaths. This connection illustrates the intertwined relationships and mutual support within the family during challenging times.

When Phoebe Ruff passed away circa 1873, leaving behind her daughters Luverna, Hester, Rebecca and Martha, the absence of a will and no surviving male heirs would have significantly impacted how her estate was handled. With the lack of a male heir or designated executor would have complicated matters, as women during this period often faced legal and social barriers in managing property independently.

The daughters, now unattached adults, would have been expected to manage their own affairs, but societal norms often pushed unmarried women into the households of extended family. If no male relative stepped forward, they might have relied on each other for economic and social support, forming a joint household or seeking aid from nearby relatives. In the absence of significant resources, they risked being labeled as destitute, potentially requiring assistance from the community or local church. The absence of a father, a will, and male heirs left the Ruff daughters in a precarious legal and social position, underscoring the challenges women faced in securing their inheritance and independence during this time.

Between 1875-1880, Hester Borden had moved to the Palestine area and was living next door to her sister Sarah A Wheeler. Her second niece Ann Garmany was living with her. Living five households away was Hester’s niece Nancy Ann Ruff Buchanan and her husband and children. This points to the probably that the Buchanan’s were living at the old Ruff Place.

The Knighten and Borden families of Borden Springs, Alabama were long-standing neighbors, with properties that often adjoined each other. Their close proximity and shared community ties suggest a strong likelihood that Hester Putnam Borden and William C. Knighten were well-acquainted, having lived near one another since at least the 1850s.

Given this connection between the two families, it raises an intriguing possibility: was it merely coincidence that the Knightens became involved in providing care for one of Hester Borden’s second nieces? This connection between neighbors and extended family deserves closer examination, as it highlights the intertwined relationships within the community and the shared responsibility for caregiving among family and neighbors during that time. The following court case further explores this fascinating dynamic.

In 1882, William C Knighten filed a petition in the March term.

Cleburne County Probate Records 1881-1884, pg 68

The State of Alabama, Cleburne County

Probate Court, Special Term March 29th 1882

This day came William C Knighten and filed a petition in writing and under oath in this court representing that Dona Ruff a female of about the age of four years is the child of one Hester Ruff who is a resident of this county and who is unable to provide for the maintenance and suport of her said minor child and who is an unfit person to have the case custody and control of said minor child. And praying that the necessary steps and proceedings be had by the judge of this court to bind and apprentice the said minor child to him the petitioner as is made and provided by statute.

It is ordered that the 5th day of April 1882 be and is hereby appointed the day upon which to hear the said application and the proff which may be submitted.

It is further ordered that the said Hester Ruff the mother of said child have due and legal notice of the filing of said petition and the nature of the same and of the day as above appointed for the hearing of said application by personal service by citation served upon her as is required by law. To appear and contest the said application if she thinks property. Signed T.J. Burton, Judge of Probate.

The court entry from 1882 reveals a significant case involving Hester Ruff, the mother of a young child named Dona Ruff, who was deemed unable to provide for her daughter’s care and support. This entry, combined with the historical evidence and family events previously discussed, presents intriguing possibilities when considering Hester Ruff’s relationship to Hester Putnam Borden and her extended family. While this case does not directly connect to Annie Garmany, it demonstrates that circumstances involving young children being placed in alternate care within the family or community were not uncommon during this time.

Given that Annie Garmany’s parentage remains unresolved, it is worth exploring whether similar situations involving relatives like Hester Ruff, who was likely one of Hester Putnam Borden’s nieces, could offer insights. While this does not suggest Hester Ruff is definitively Annie’s mother, the historical context and familial ties suggest this line of inquiry is worth pursuing. Such situations, where extended family members played significant roles in caring for or placing children in guardianships or apprenticeships, were prevalent and should be further researched to uncover potential connections.

In 1874, Phoebe Putnam Ruff’s daughters—Luverna Ruff, Rachael Ruff, Hester Ruff, Rebecca Ruff, and Martha Ruff—all meet key criteria that make them strong candidates for further investigation in connection to Annie Garmany’s lineage. Each of these women would have been over the age of 18, unmarried, and born in Alabama, aligning closely with what is known about Annie’s possible mother. These factors provide compelling reasons to explore their lives more deeply, as they meet much of the demographic and situational criteria necessary to be considered. The overlap of age, marital status, and geographic location creates a strong case that these daughters should be examined more thoroughly to determine if one of them could be Annie’s mother. Given these good odds, their stories and records deserve a closer look to uncover potential connections.

Leave a comment