The “name’s the same fallacy” is a common pitfall in genealogical research where a family genealogist assumes that two individuals with the same name are the same person. This fallacy arises from the mistaken belief that identical names across different records indicate the same individual, neglecting the broader context and additional corroborative details needed for accurate identification.

Confirmation bias is a cognitive bias where individuals favor information that confirms their preexisting beliefs or hypotheses while disregarding or downplaying evidence that contradicts them. In genealogy, this bias can manifest when researchers selectively gather or interpret data that supports their desired family narrative, leading to skewed or inaccurate conclusions. For example, a genealogist might fixate on a census record that seemingly matches their ancestor’s name, ignoring discrepancies in age, location, or other identifying details that suggest a different person. This bias can significantly undermine the integrity of genealogical research, as it blinds researchers to the full scope of available evidence.

The name’s the same fallacy often leads to confirmation bias in genealogical research. When genealogists prematurely conclude that two records pertain to the same individual based solely on a shared name, they set the stage for confirmation bias by forming an initial, unsupported assumption. As they continue their research, they may subconsciously prioritize information that supports this assumption, reinforcing their initial mistake. For instance, having identified a census record with a matching name, they might disregard contradictory evidence from other records or rationalize inconsistencies to fit their narrative.

The Assumption

Isaiah Smith Jr, born around 1816, first appears by name in historical records through an 1847 marriage record in Dooly County, Georgia. It is presumed that Isaiah Smith Jr (approximately 31 years old) married Permelia Harthcock (around 23 years old) in Dooly County.

Isaiah Smith Jr’s father, Isaiah Smith Sr, had moved to Dooly County from neighboring Houston County around 1840. Isaiah Smith Jr subsequently appears in the 1850 U.S. Census for Dooly County, Georgia.

After 1850, Isaiah Smith Jr does not appear in the 1851 Dooly County Tax record, suggesting he had left Dooly County by that time.

Family genealogists searching for records of Isaiah Smith Jr before his 1847 marriage have focused on the 1840 U.S. Census for Jefferson County in the Territory of Florida, the 1845 Election Returns for Jefferson County, and the compiled service records of Florida Militiamen during the Second Seminole War.

These family genealogists have propagated the idea that the Isaiah Smith Jr listed in these Florida records is the same individual as the Isaiah Smith Jr from Dooly County, born in 1816.

The Records

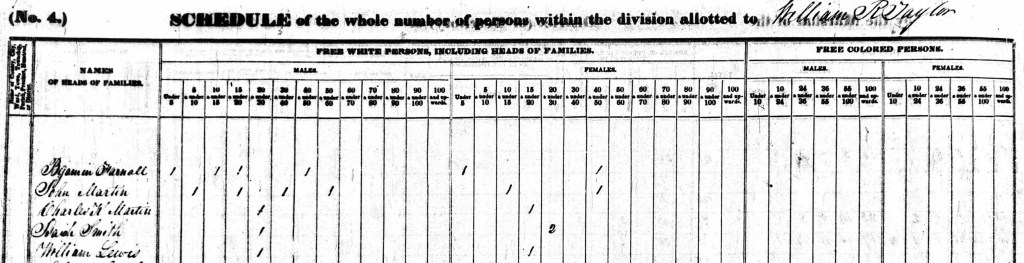

1840 Census

The 1840 U.S. Census shows an Isaiah Smith living in Jefferson County. The household consists of one male aged 20-30 and two females aged 20-30.

The argument is that the age of the male (20-30) matches exactly the age Isaiah Smith Jr would be in 1840, assuming he was born in 1816, making him 24 years old. Additionally, the two females aged 20-30 are claimed to be two of his older sisters, born between June 1810 and May 1815. These approximate birth ranges are derived from the 1830 U.S. Census for Isaiah Smith Sr.

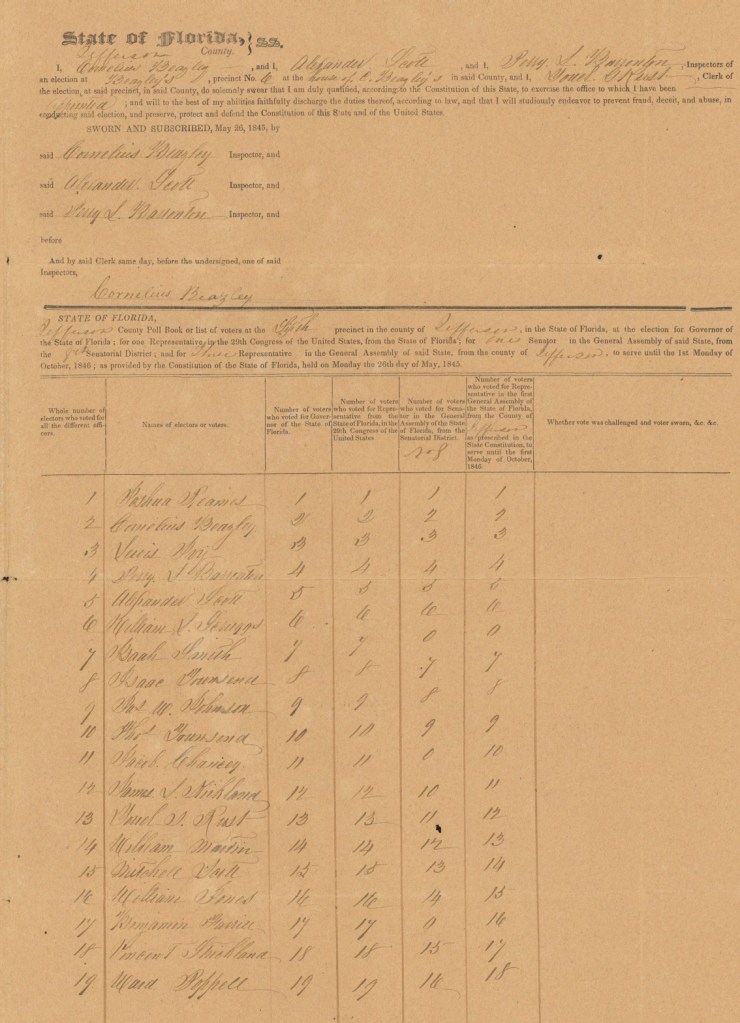

1845 Election Returns

The 1845 Election Returns for Florida, marked the first statewide election, show an Isaiah Smith registered as a voter in Jefferson County, Precinct 6. The voting took place at the house of Cornelius Beasley.

The argument is that this Isaiah Smith from the 1845 return for Jefferson County is the same individual listed in the 1840 Census, who is also the Isaiah Smith Jr from Dooly County, born in 1816.

Milita Rolls

The militia rolls documenting the 2nd Seminole War reveal multiple enlistments of an Isaiah Smith across different companies during the conflict.

The argument posits that this Isaiah Smith is the same individual found in the 1845 Election Returns and the 1840 census, all corresponding to the Isaiah Smith Jr from Dooly County, born in 1816.

| No. | Rank | Muster In Date | Where | Military Unit | Muster Out Date |

| 1 | Private | 29 Dec 1935 | Monticello | Capt. Abram Bellamy’s Co., FL Mtd Vols | 10 Feb 1835 |

| 2 | Private | 3 Mar 1836 | San Pedro | Lt. Patterson’s Det., 13 Reg’t, 1st Brig., FL Mtd Militia | 14 Jul 1836 |

| 3 | Private | 10 May 1836 | Tallahassee | Capt. Fisher’s Co. 7th Reg’t, 1 Brig, FL Mtd Militia | 10 Nov 1836 |

| 4 | Private | 27 Mar 1838 | Jefferson Co . [absent with leave] | Capt. Shehee’s Co. Taylor’s Batt. Middle FL Mtd Vols | 9 Jun 1838 |

| 5 | Private | 9 Jun 1838 | Camp Wacissa | Capt. Rowell’s Co., 1st Reg’t Florida Mtd Militia | 17 Nov 1838 |

| 6 | Private | 4 Jul 1838 | Monticello | Capt. Smith’s Co., 9th Reg’t, 1st Brig. FL Mtd Militia | not listed |

| 7 | Private | 3 Mar 1839 | Camp at the Sand Ford (Oscilla) | Capt. Rowell’s Co., FL Mtd Vols | 4 Sep 1839 |

| 8 | Private | 23 Sep 1839 | Camp Call | Capt. Newbern’s Co., FL Mtd Vols | 20 Dec 1839 |

| 9 | Corporal | 10 Aug 1840 | Camp Call | Capt. Townsend’s Co., 1st Reg’t (Bailey’s), FL Mtd Militia | 16 Nov 1840 |

| 10 | Corporal | 9 Dec 1840 | Camp Townsend | Capt. Redding’s Co., (1st Service), 1st Reg’t, FL Mtd Militia | 13 Mar 1841 |

| 11 | Private | 14 Mar 1841 | Charles Ferry | Capt. Redding’S Co., (2nd Service), 1st Reg’t, FL Mtd Militia | 15 Apr 1841 |

The Falsification

Falsification is the process of testing a hypothesis or belief by looking for evidence that could prove it wrong. In the context of genealogy, this means actively seeking out records or information that could contradict a previously held assumption or conclusion. The goal is to ensure that the genealogical research is robust and not solely based on selective evidence that supports a preconceived notion.

In hand with falsification is disconfirmation. Disconfirmation involves finding and acknowledging evidence that goes against one’s current hypothesis or belief. In genealogy, disconfirmation is a critical practice because it helps researchers avoid the trap of confirmation bias. By identifying and considering evidence that challenges their assumptions, genealogists can re-evaluate their conclusions and ensure that they are based on a comprehensive and balanced assessment of all available data.

There are several pieces of evidence in the form of historical records that many family genealogists may not be aware of. These records are found within the “Election Records Jefferson County, 1828-1865”.

A poll book is an official ledger used during elections to record the names of voters who have cast their ballots. It serves as a historical record and verification tool for the electoral process. Typically, a poll book contains the names of all registered voters who participated in the election, sometimes along with other details such as the order in which they voted, their addresses, and signatures. It can also include the vote count for each candidate or issue on the ballot. The poll book would have been used to ensure the integrity of the election, verifying that all votes were cast by eligible voters and that the election was conducted fairly.

In the mid-19th century, voting requirements in the United States varied significantly by state and locality, reflecting the evolving nature of American democracy. In Florida, as in many other states, voters were typically required to reside in the precinct where they intended to cast their ballots. This residency requirement often mandated that individuals live in their precinct for a minimum duration, which could range from a few months to a year, ensuring that voters had a genuine connection to their local community.

Age and registration were also critical factors. Voters had to be at least 21 years old, aligning with the broader national standards of the time. Additionally, potential voters were often required to register in advance of the election, providing proof of residency and eligibility to participate in the electoral process. This pre-registration process was intended to maintain the integrity of the vote and prevent fraud. Although some states had property ownership requirements for voting, by the 1850s and 1860s, many had begun to move away from these restrictions, gradually expanding the electorate.

The compilation of these records are below.

| Election Date | Name | Precinct | |

| 4 May 1829 | Isia Smith | #2nd – Edwin Rogers’ House | Joshua Robinson, Moses Richardson, Hinsen Wilder, Elias Edwards |

| 7 November 1831 | Isaiah Smith | #4th – Hurst Hagan’s House | Joshua Robinson, Moses Richardson, Hinsen Wilder, Elias Edwards, R C Hurst |

| 1839 | Isa Smith | unable to determine | William Beasley, Robert Beasley, Paul Poppell |

| 1 May 1843 | Isaiah Smith | – Cornelius Beasley’s House | William Beasley, Paul Poppell, Cornelius Beasley |

| 6 November 1843 | Isiah Smith | – Cornelius Beasley’s House | Paul Poppell, Cornelius Beasley, |

| 6 October 1845 | Isaiah Smith | – C Beasleys House | Cornelius Beasley, Paul Pappell |

| 2 October 1848 | Isaiah Smith | #2nd – Monticello, Court House | {Cornelius Beasley & Paul Pappell appears in 8th precinct |

What this compilation shows is that starting from 1829 there is an Isaiah Smith living in Jefferson County which is part of the Territory of Florida. In 1829 this Isaiah Smith would appear to be at least 21 years of age. Previous voting records for Leon County, Florida were examined and there is no mention of an Isaiah Smith. (Jefferson County formed from Leon County on 19 January 1828)

Through the seven instances of voter polls there is only one instance of an Isaiah Smith listed on the year of record. This would suggest that the Isaiah Smith first listed on the 1829 poll is the same Isaiah Smith listed on each succesive poll.

The Refutation

Refutation refers to the act of disproving or invalidating a hypothesis, belief, or assumption by providing evidence that contradicts it. In genealogy, refutation occurs when new records or information are discovered that challenge or undermine a previously held conclusion. This process is essential for maintaining the integrity and accuracy of genealogical research, as it allows researchers to correct errors, revise interpretations, and refine their understanding of familial relationships.

When genealogists encounter evidence that refutes their initial hypotheses, they must carefully evaluate the new information and adjust their conclusions accordingly. By incorporating refutation into their research methodology, genealogists can ensure that their family trees are based on sound evidence and reflective of the complexities and nuances of historical records.

Recalling from the main ‘assumption’, the argument is that Isaiah Smith Jr from Dooly County would be the Isaiah Smith listed in the 1840 U.S. Census for Jefferson County, the 1845 Voter Returns and the 2nd Seminiole Muster Rolls.

The 1840 census assumption contains the largest confirmation bias.

Age reporting accuracy in U.S. census records is a crucial consideration for genealogists navigating the intricate pathways of family history. However, delving into these historical documents unveils a myriad of challenges that can obscure the true identities of individuals. One prominent issue stems from the inherently fallible nature of human memory. Age, often provided based on recollection, is susceptible to the passage of time, rendering it prone to inaccuracies, particularly among older individuals or those reporting on behalf of others.

Compounding this challenge is the variability introduced by different census takers, or enumerators, tasked with recording demographic details. Each enumerator brings their own interpretation and articulation to the task, leading to inconsistencies in age reporting across different records. Moreover, changes in instructions given to enumerators over time further exacerbate these discrepancies, as adherence to varying protocols may yield divergent outcomes in age documentation.

Cultural and linguistic factors also play a significant role in shaping age reporting practices. In some communities, especially rural or less literate populations, the precision of age recording may be diminished, reflecting broader societal norms and practices. Accents or language differences can further muddle the process, as enumerators may mishear or misinterpret age information provided by respondents, inadvertently distorting the data.

The dynamic nature of age itself presents yet another layer of complexity. Individuals may report different ages across successive censuses, a phenomenon compounded by variations in census-taking timings throughout the decades. These temporal nuances, coupled with the potential for omitted or estimated ages when exact information is lacking, underscore the intricate dance between time and documentation.

As genealogists navigate this labyrinth of age reporting intricacies, they must approach census records with a critical eye, recognizing the multifaceted factors that shape the veracity of age data and employing meticulous scrutiny to unravel the threads of familial history.

The confirmation bias surrounding the 1840 census data warrants closer examination. This bias is so narrow in focus that it overlooks the possibility of alternative explanations. For instance, while comparing the 1830 U.S. Census data for Isaiah Smith Jr could shed light on how it might correspond to the individual in the 1840 Jefferson County census, it’s important to consider a subjective disconfirmation approach. In this regard, the presence of a Solomon Smith in the 1830 U.S. Census for Jefferson County, already living in the area, introduces another possibility. Given the potential discrepancies in census ages, it’s plausible that one of the younger males and both females from Solomon Smith’s household could logically correlate to the individuals recorded in the 1840 census.

This demonstration aims to illustrate that the bias stemming from Dooly County may not necessarily be accurate, as there are other similar scenarios that could explain the discrepancies.

The 1829-1865 voting records provide further refutation of the claim. If we presume that the 1829 voter poll for Isaiah Smith refers to Isaiah Smith Jr from Dooly County, it would imply that he was a 13 year old boy and a documented voter, which is highly improbable. Similarly, in the 1831 record, he would have been just 15 years old. These scenarios are unlikely to be accurate, casting doubt on the assumption that the Isaiah Smith in these records is the same individual born in 1816.

In light of this new evidence, asumptions that have repeatedly been propagated throughout the genealogy community about Isaiah Smith Jr are likely not true.

What is likely the reality is that the Isaiah Smith living in Jefferson County in 1829 is the same Isaiah Smith that is in all the voter poll books for Jefferson County, previous detailed. He is likely the same Isaiah that is listed in the 1840 U.S. Census for Jefferson County and he is likely the same Isaiah Smith that is listed through the Militia Rolls for and served / mustered in, in locations in or adjacent to Jefferson County.

Leave a comment