In the mid 1800s, the United States was experiencing an era of tremendous growth, marked by a fundamental economic difference that existed between the country’s northern and southern territories.

In the North, a robust manufacturing and industrial sector flourished, while agriculture predominantly consisted of small-scale farming operations. In contrast, the South’s economy revolved around large-scale farming, heavily reliant on the labor of enslaved Black individuals to cultivate key crops such as cotton and tobacco.

As abolitionist sentiments gained momentum in the North after the 1830s and opposition to the expansion of slavery into new western territories grew, many southerners grew apprehensive about the future of slavery—an institution integral to their economy.

The pivotal event of abolitionist John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry in 1859 further fueled southern fears of northern aggression against their economic backbone, the institution of slavery. Abraham Lincoln’s election in November 1860 served as a tipping point, prompting seven southern states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—to secede from the Union within three months.

On April 12, 1861, the American Civil War commenced as Confederate artillery initiated the first shots of the conflict in the bombardment of Fort Sumter situated in Charleston, South Carolina. Following the Confederacy’s capture of Fort Sumter, four additional southern states—Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee—subsequently joined the Confederacy.

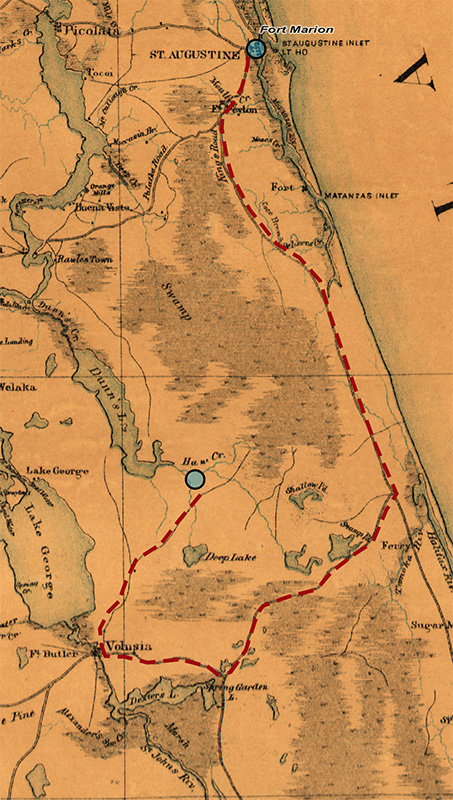

In the initial phases of the Civil War, St. Augustine, Florida, emerged as a crucial site for recruiting and organizing new Confederate troops. Its strategic proximity to major Confederate strongholds such as Jacksonville and Fernandina further bolstered its importance as a military hub.

Richard Calhoun Smith and his brother Hardy Smith volunteered and enlisted in the Confederate Army on 18 November, 1861 as indicated on several Muster Rolls for Company D of the 8th Florida regiment.

Richard and Hardy Smith’s decision to enlist was likely influenced by various factors, with economic considerations being prominent, especially in agricultural regions like Volusia County. Military service offered the promise of steady pay and access to essentials such as food and clothing, which would have been particularly appealing amidst wartime shortages. Additionally, social pressures and peer influence likely played a significant role, as was common in close-knit communities of the time. The expectation of loyalty and duty among young men compelled individuals like Richard Smith to align with friends, family, and community norms by enlisting. Furthermore, a deeply ingrained sense of duty and honor, instilled through upbringing and cultural values, motivated many to join the Confederate ranks. For Richard Smith and others, serving in the military was seen as a noble obligation to safeguard their families, communities, and Southern way of life from perceived threats posed by Union forces.

Hardy and Richard Smith traveled to St. Augustine to present themselves to recruiting officers, undergo medical examinations, and sign enlistment papers. The process of enlisting usually involved taking an oath of allegiance to the Confederate States of America and agreeing to serve for a specified period of time, typically for the duration of the war.

After enlisting, volunteers would typically be assigned to a specific unit and undergo basic training before being deployed to the front lines or other areas of military operations. Hardy and Richard Smith were assigned to Captain Baya’s Independent Company, Grayson’s Artillery. It is reasonable to assume that Richard and Hardy Smith underwent some form of basic training at Fort Marion, situated in St. Augustine.

Richard and Hardy Smith were charged with managing and operating artillery weapons to provide support to infantry and cavalry forces on the battlefield. This responsibility is corroborated by their Muster Roll cards, with Richard Smith further affirming his role as an artilleryman in the 8th Florida Artillery in his pension application. However, this role likely changed to an infantry role as Richard Smith was shipped to the front lines.

In the summer of 1862, Richard and Hardy Smith were organized as Company D of the 8th Florida regiment. This company along with the 2nd Florida Company H were made up mostly of men from St. Johns and Volusia Counties. The 8th Florida was then organized with the 2nd and 5th Florida regiments and assigned to Edward A. Perry’s newly formed Florida Brigade. Perry’s Brigade would soon be sent to the front lines and expiernence their first exposue to war.

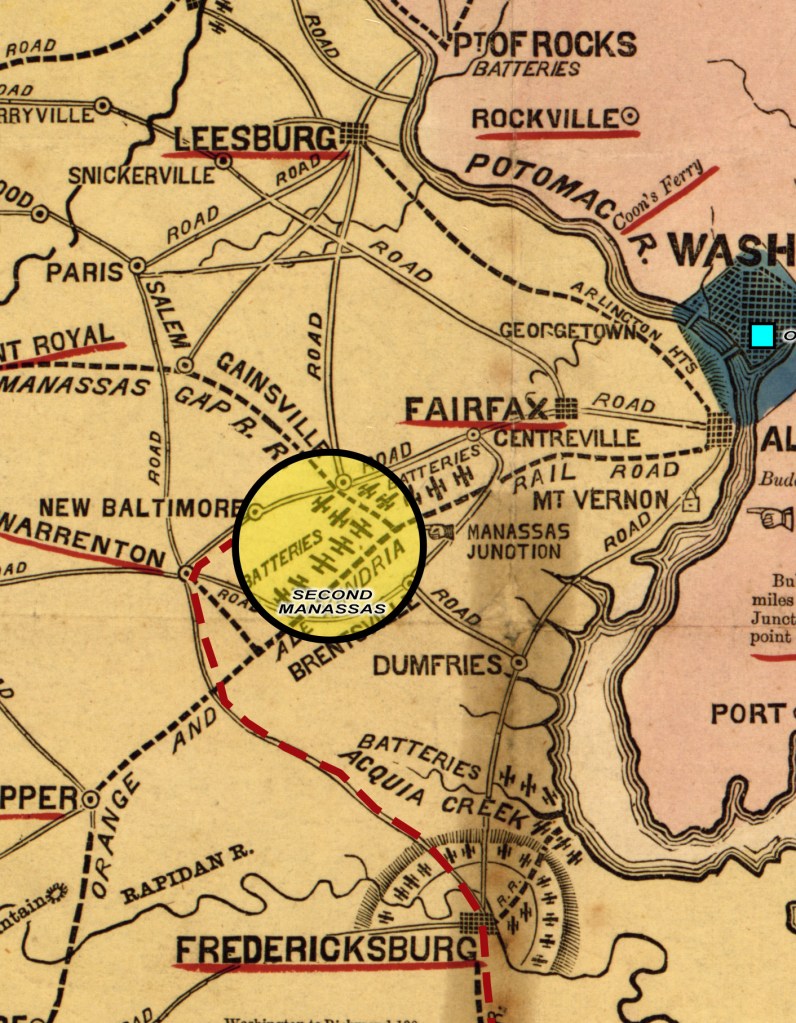

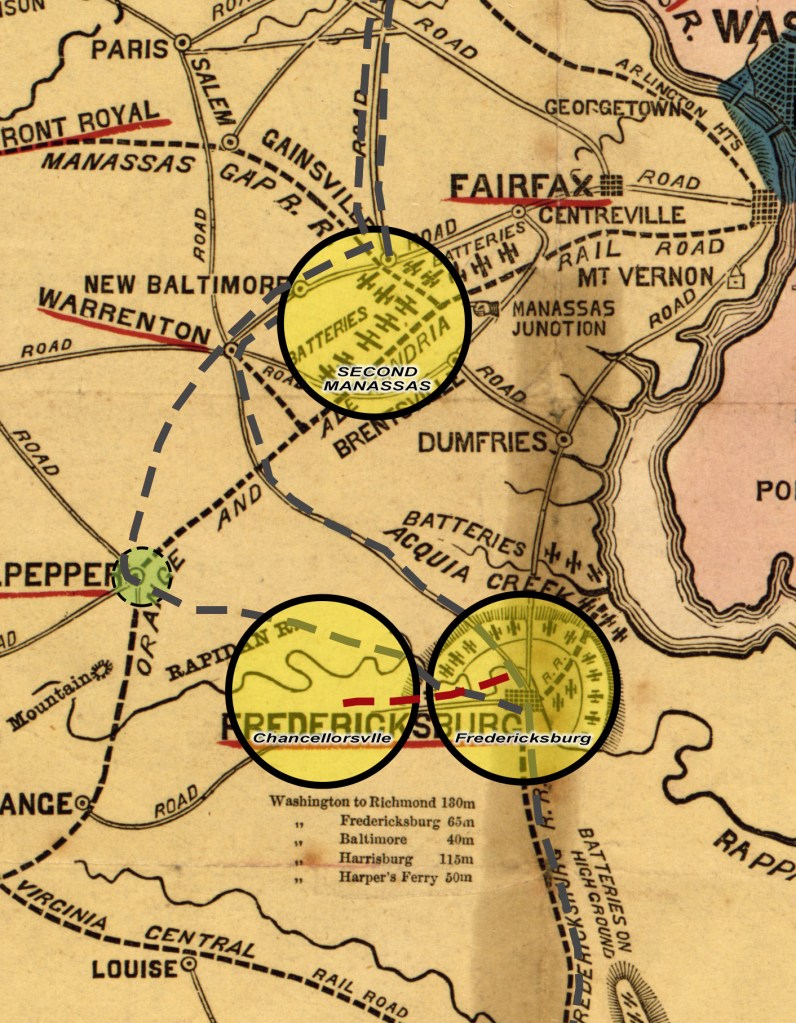

Battle of Second Manassas

[Longstreet > Wilcox > Pryor > Perry > Baya > 8th D]

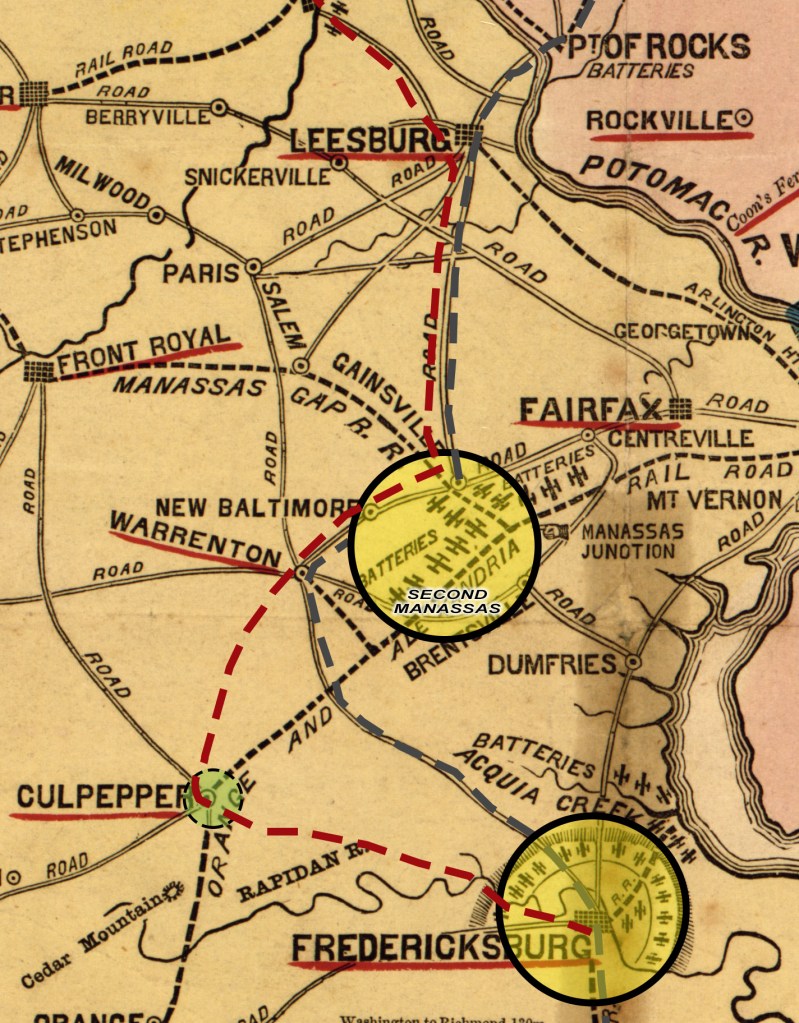

Perry’s Brigade reached the battlefield in progress on 29 August 1862. Perry’s Brigade served under Brigadier General Roger A. Pryor’s Brigade under Brigadier General Cadmus Wilcox’s Division of the First Corps, under Major General James Longstreet.

During the final stages of this engagment, Longstreets First Corps charged into Pope’s Army which eventually forced Pope’s Army to flee.

It is assumed that Richard and Hardy Smith were not actively engaged in this effort. As history indicates, it appears Pryor and Brigadier General Winfield Scott Featherston’s Brigades were held in safety in the Groveton woods during the encounter.

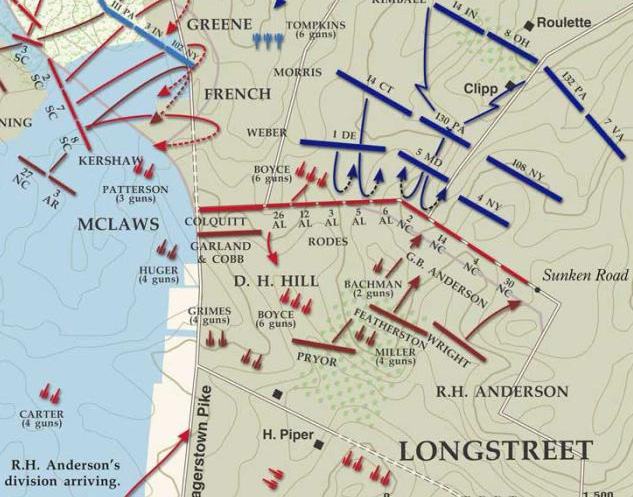

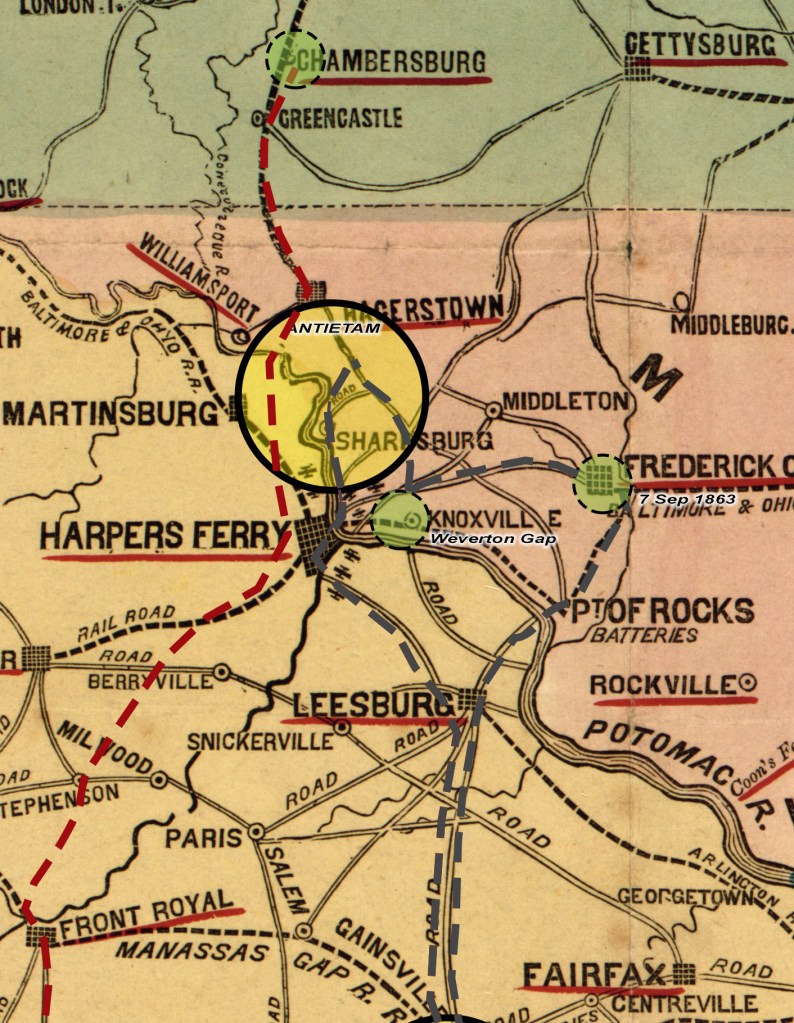

Battle of Antietam

[Longstreet > Anderson > Pryor > Perry > Baya > 8th D]

From Manassas the 8th Florida marched north crossing the Potomac River near Leesburg and reached Frederick, Maryland on the morning of 7 September 1683. The brigade was still commanded by Roger Pryor, but now was assigned to Major General Richard H. Andersons division in Longstreets wing.

A few days later Pryor’s brigade would be positioned at Weverton Gap to guard the backdoor for Major General Thomas Jonathan ‘Stonewall’ Jackson’s assualt on Harpers Ferry.

Jackson secured the victory at Harpers Ferry and before the dust could even settle he gathered the majority of the Army and made a ardous fast paced march north to Sharpsburg covering about 30 miles in 2 days.

The Battle of Antietam commenced on 17 September 1683 north of the town of Sharpsburg. Andersons division moved into position about mid day and the 8th Flordia along with the 2nd and 5th Flordia was poistioned in a cornfield on the north side of the orchard supporting the North Carolina regiments fighting along the Sunken Road.

The Florida brigades suffered many casualties as a result of being at the center. Of the approximately 570 Floridians who entered the battle 282 became casualties, a loss of approximately 50 percent. Antietam was the first real engagement for the 5th and 8th Florida, and considering their rookie status, it seems remakrable that they fought as well as they did.

Among the Floridian casualties, there were 91 killed, 84 wounded, and 107 missing. Specifically, the 8th Florida regiment accounted for 25 killed, 24 wounded, and 28 missing soldiers. Richard Smith, as noted in his pension papers, claimed to have never been injured. Hence, it is reasonable to infer that Richard Smith is among the approximately one hundred 8th Florida soldiers who survived without injury.

In November 1862, due to their diminishing numbers, the three Florida brigades were amalgamated, with Colonel E.A. Perry assuming command. Captain David Lang took charge of the 8th Florida regiment. Perry’s brigade continued to serve in Anderson’s Division of Longstreet’s First Corps.

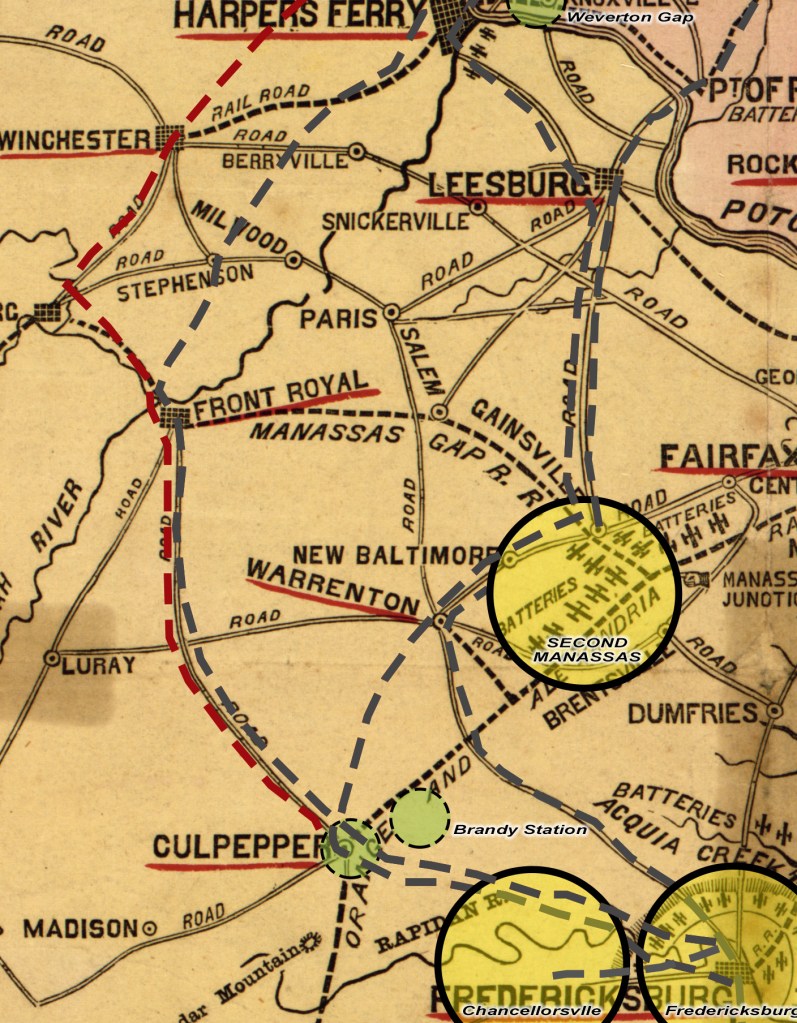

Battle of Fredericksburg

[Longstreet > Anderson > Perry > Baya > 8th D]

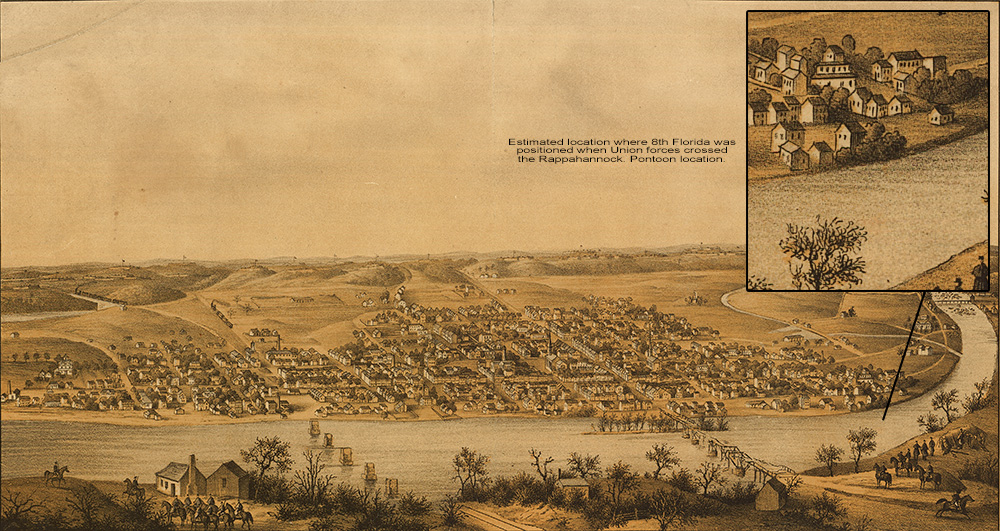

Longstreets First Corps recrossed the Potomac River and marched to Culpepper where they rested for a period of time. Then by 11 December 1863 Longstreet’s First Corps moved to Fredericksburg to try and prevent the Union army from crossing the Rapahannock River.

The 13th, 17th, 18th and 21 Mississippi regiments were dispatched to the old city to harass and make it costly for the Union in their attempts at a pontoon river crossing.

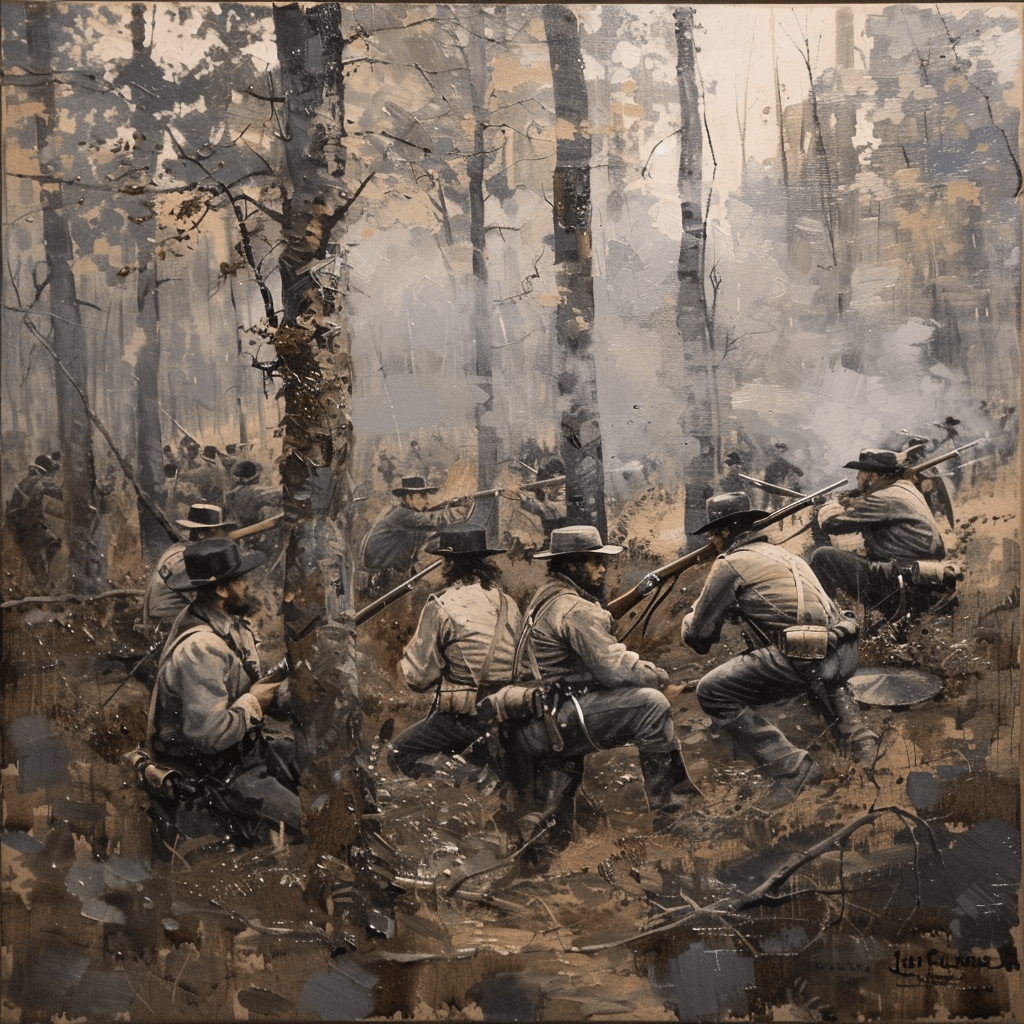

The 8th Florida regiment was also sent to support the Mississippians. Captain David Lang, the unit’s senior officer, directed the regiment at Fredericksburg. Lang received orders, at about 5 a.m., to take his unit “to a point on the river forming the site of the old ferry” to support Lt. Col. John C. Fiser’s Seventeenth Mississippi at Hawke Street. Brigadier General William Barksdale, overseeing the Mississippi regiments, intercepted the 8th Florida, dividing the regiment into two sections. Barksdale ordered Companies A, D, and F, commanded by Captain William Baya, to reinforce his troops in opposing the crossing near the destroyed railroad bridge.

Baya’s unit swiftly moved to support Captain Andrew R. Govan’s section of the Seventeenth Mississippi regiment, which was tasked with guarding the center of town. While Govan kept his troops sheltered, partly protected by Fredericksburg’s cellars and buildings, he dispatched Baya to an open area on the west bank of the river. Throughout the day, Baya grew increasingly uneasy about opening fire on the Union from this vulnerable position. Govan expressed frustration that the Floridians “repeatedly failed to obey my commands when ordered to fire on the bridge builders.” According to a modern historian’s assessment, “Baya repeatedly disobeyed orders and refused to fire on the pontooneers for fear of attracting attention from the Federal artillery.” By 2:00 p.m., Baya informed Govan that his Florida troops could no longer maintain their position along the riverbank, and he had decided to withdraw from the exposed area.

Perhaps fearing the stigma of cowardice, Baya hesitated but ultimately stuck to his untenable position. At 3:00 p.m., the Union unleashed a furious artillery barrage on the Southern troops guarding Fredericksburg. Fifteen minutes later, the 89th New York crossed the Rappahannock in unused pontoons, landing near the city docks, and swiftly advanced through the city. Govan promptly withdrew his Mississippians to Caroline Street, but failed to communicate his retreat to Baya. It didn’t take long for the New Yorkers to overpower Baya’s Floridians, now left isolated. Following a brief skirmish, the heavily outnumbered 8th Florida had little choice but to surrender. The Union captured twenty-two Floridians, including Captain William Baya, Richard Smith, and Hardy Smith.

After the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Confederate Army held its ground on the west bank of the Rappahannock River, while the Union Army remained positioned on the east bank. The surviving members of the 8th Florida regiment remained in the Fredericksburg area, located to the north of the city.

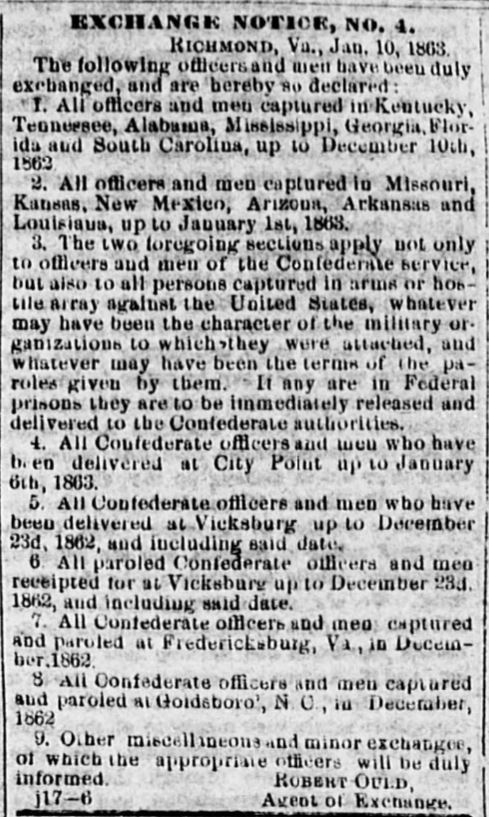

Richard and Hardy Smith were likely part of the approximate 276 Confederate prisoners that were exchanged within weeks of their capture. (The Savannah Republican, 1 January 1863)

When soldiers were captured on the battlefield, they were usually taken prisoner by the opposing side. Once captured, soliders would be processed and registered as prisoners of war. In many cases, captured soldiers were then paroled, meaning they were released from captivity upon their promise not to take up arms again until formally exchanged.

Exchange points, were often located along the front lines or in neutral territory, were designated for the exchange of prisoners. Upon arrival at the exchange point, paroled prisoners would be verified and processed by representatives from both sides to ensure compliance with the terms of the exchange agreement.

This exchange likely occurred at a neutral camp near or at Falmouth, Virginia and presumbably within the last two weeks of December 1862, while both armies where in winter camp at Fredericksburg. This is evident from muster rolls and is supported in part by the service records of Philip L. Gomez and Emanuel Dugger, both of whom were captured with the 8th Florida at Fredericksburg and subsequently killed in action at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 3, 1863. Also, Captain Baya is recorded being promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on 9 January 1863.

Over the following two months, while encamped north of Fredericksburg, Hardy Smith fell ill, presumably due to poor camp conditions.

Lynchburg, Virginia, served as a significant medical center and logistical hub for the Confederate army during the Civil War. The city was home to several Confederate hospitals, including the General Hospital No. 1, which was one of the largest military hospitals in the South. Additionally, Lynchburg was strategically located along key railroad lines, making it an important transportation hub for moving wounded and sick soldiers from the front lines to medical facilities further south.

It’s likely that Hardy Smith was transported to one of the hospitals in Lynchburg (Lynchburg’s Civil War Hospitals) for treatment after falling ill, where he received medical care before ultimately passing away on 3 April 1863.

Hardy Smith’s cause of death was listed as disease, rather than injury sustained in battle, it’s likely that he succumbed to an illness rather than wounds received in combat. The most common diseases and illnesses that afflicted soldiers during the Civil War included infections, respiratory diseases like pneumonia, dysentery, typhoid fever, and various other contagious diseases spread in crowded military camps and hospitals. Without specific details from his medical records, it’s challenging to determine the exact disease Hardy Smith contracted, but given the time frame and conditions of the period, possibilities could include infections, respiratory illnesses, or gastrointestinal ailments.

Hardy Smith was buried in Old City Cemetery, Lot 199 Row 1 Grave 5 which is located in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Hardy Smith was the second child of John W. Smith and Nancy A. Smith and namesake to Nancy Smith’s presumed father, Hardy Smith Sr (1757-1854).

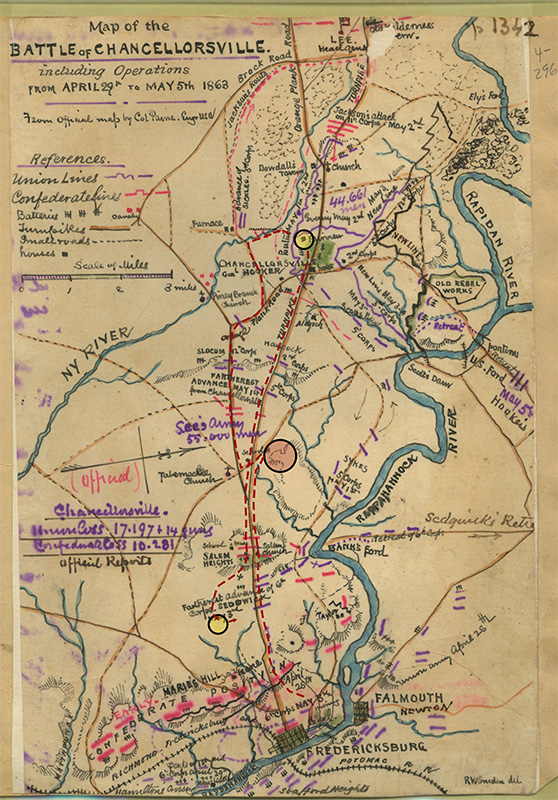

Battle of Chancellorsville

[Longstreet > Anderson > Perry > Baya > 8th D]

Less than a month after Hardy Smith’s passing, the Union army from their poisition at Fredericksburg attempted to skirt the Rappahannock River marching north to cross the river. Their plans were to cut off the Confederate’s and attack the troops remaining at Fredericksburg from the rear.

On 30 April 1863 this plan was thwarted with troops from Fredericksburg engaging the Union at Chancellorsville.

The 8th Florida’s involvement in the early encounter amounted to a light skirmish.

By 3 May the 8th Florida marched towards Catharines Furnance and then grouped a little to the southeast of Hazel Grove. Then Perrys Floridans sacked the Union position at Fairview.

Then on the morning of 4 May, Andersons division including Perry’s Floridians rushed back towards Fredericksburg to help defeat the enemy that had poisitioned northwest of Marye’s Heights. During the engagement the Floridians received orders to charge a Union battery of 12 guns across an open field. Luckily, a mix up spared the Floridians as Perry’s troops began the advance, Ran Wrights Georgia brigade cut between the battery and the Floridians. By the time the lines were untangled, the Union guns had been withdrawn.

Perry’s Floridian’s returned to the town of Chancellorsville after the encounter. Andersons division would get realigned under Ambrose Powell Hill’s new Third Corps.

Battle of Gettysburg

[Hill > Anderson > Perry (Lang) > Baya > 8th]

Hill’s Third Corps remained stationed near Fredericksville, tasked with preventing the Union army from crossing the Rappahannock. In the ensuing weeks, multiple skirmishes erupted between the opposing forces. However, on June 14, 1863, the Third Corps received orders to proceed westward and reunite with Lee’s Army.

Over the subsequent fortnight, they endured a taxing march, heading west and north until they reached Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where they finally found a brief respite.

On the morning of July 1, 1863, Anderson’s Division departed from Chambersburg en route to Gettysburg, where the two armies would once again collide. Positioned at Herr Ridge on the first day of battle, Anderson’s troops awaited the unfolding conflict. By the following day, they advanced further toward Seminary Ridge.

By July 2, 1863, Perry’s Floridians, under the command of David Lang, found themselves locked in combat near Cemetery Ridge, situated between Spangler’s Woods and Emmitsburg Road. Engaging the enemy at Emmitsburg Road, they managed to push them back toward Cemetery Ridge. However, as the Union forces began to scatter, Lang observed the enemy maneuvering to flank his men, prompting a reluctant order to retreat to Emmitsburg Road. Despite attempting to form a defensive line, the inadequate cover offered by the road compelled them to fall back further to Spangler’s Woods, where they remained through the night.

The charge to Cemetery Ridge exacted a heavy toll, resulting in 300 casualties, representing approximately 40 percent of Lang’s overall strength.

On July 3, 1863, Lang’s troops launched a second assault on Cemetery Ridge. However, amidst the chaos and mounting casualties, they were compelled to withdraw once again, suffering an additional 20 percent loss in men.

Of the 742 men who marched toward Gettysburg on July 1, 461 had either been killed, wounded, or captured. The brigade endured a staggering 62 percent loss in strength, reportedly the highest casualty rate among Confederate brigades during the Pennsylvania campaign. The 2nd Florida suffered 146 casualties, the 5th Florida lost 195 men, and the 8th Florida incurred 120 killed, wounded, or captured.

On July 4, the Confederate Army commenced its withdrawal from Gettysburg, retracing their steps through grueling marches amidst rain and muddy roads. After weeks of arduous travel, they finally found respite upon reaching Culpeper.

On August 1, the Florida brigade participated in a skirmish at nearby Brandy Station and Culpeper. Lang’s brigade, comprising 160 engaged soldiers, suffered 29 casualties, including 6 killed. With the Florida brigade numbering only 250 men, the loss of 29 soldiers was significant.

Richard Smith and the 8th Florida regiment remained actively engaged in the northern battlefront over the following year. From Brandy Station, the regiment participated in various conflicts, including the Bristoe Campaign (Oct 1863), Mine Run Campaign (Nov-Dec 1863), Battle of the Wilderness (May 1864), Battle of Spotsylvania Court House (May 1864), Battle of North Anna (May 1864), Battle of Cold Harbor (Jun 1864), and the Petersburg Siege (Jun 1864 – April 1865).

During the Petersburg Siege, which comprised several smaller conflicts in defense of Petersburg, the 8th Florida, including Richard Smith, was involved in engagements such as Weldon Railroad (Jun 1864), Ream’s Station (Jun 1864), and the Battle of Globe Tavern (August 1864).

During the American Civil War, furloughs were temporary leaves of absence granted to soldiers by their commanding officers, allowing them to return home for a specified period of time. Furloughs served several purposes and were an important aspect of maintaining morale and supporting the well-being of Confederate soldiers. The frequency with which furloughs were granted varied depending on factors such as the availability of manpower, the state of the war effort, and the policies of individual commanders.

According to Richard Smith’s service records, he was granted a furlough sometime after 22 January 1865.

Alabama, Texas, and Virginia, U.S., Confederate Pensions, 1884-1958

"I had a ferlow of 30 days and could not get back. Left on {illegible} furlow to go home and could not get back to my command on account of high water some places and the yankees at other places between me and my command and had me cut off and held me cut off untill the close of war. I tried all the time to get home but could not."

The American Civil War officially ended on 9 April 1865.

Leave a comment